Ruthenians in Vilnius

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania arose in an ethnic and religious borderland, in the Baltic-Slavic contact zone.1See: Aleksander Krawcewicz, “Stosunki religijne w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XIII wieku i początkach XIV stulecia”, in: Między Rusią a Polską Litwa. Od Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego do Republiki Litewskiej, pod red. Jerzegy Grzybowski, Joanna Kozłowska, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2015, s. 41–48. This ethnic polyphony made it impossible for state policy to support only one of the religious groups.

The situation of the Ruthenian community in the GDL was regulated by a number of privileges of the years 1387, 1413, and 1432.

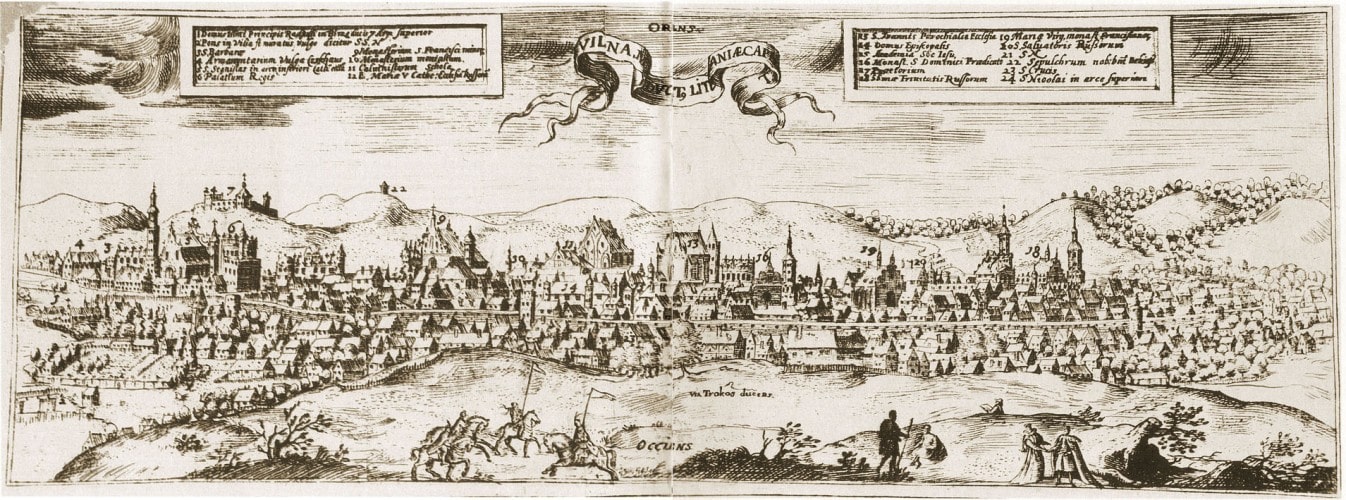

The level of urbanization in this area of Eastern Europe was insignificant. Only in the 16th century did the number of cities in Lithuania start to grow noticeably. Researchers reckon that there were approximately 220 urban centers in the country in the middle of this century. The largest and most famous was Vilnius, which was quickly growing and where, according to the calculations of researchers, 10 thousand people lived in the 16th century,2Paula Wydziałkowska, “Historia Wilna w XVI–XVIII wieku”, in: Koło Naukowe Muzealnictwa i Zabytkoznawstwa, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, available at: http://kolomuz.umk.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Paula-Wydzia%C5%82kowska-Historia-Wilna-w-XVI-XVIII-wieku.pdf, accessed: 2021 11 01; Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 19. and, at the end of the 17th century, the city and its suburbs numbered 20 thousand people3David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth Century Wilno, Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 2013, р. 7, 428. See also: David Frick, “Five Confessions in One City: Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern Wilno”, in: A Companion for Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern World (series: Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition, t. 28), ed. Tomas Max Saftey, Leiden: Brill, 2011, p. 422. [1].

Vilnius, which arose in the 13th and 14th centuries, was located on the border of two ethnic areas, Lithuanian and Ruthenian, which because of a number of circumstances were in the 14th century united within one state. Irma Kaplunaite writes that the Orthodox, the majority of whom were Ruthenians, settled on the territory of the future capital in the last quarter of the 13th century, during the rule of Traidenis, while the Catholics came to the city from the end of the 13th to the start of the 14th centuries. And, though Orthodox and Catholics settled in Vilnius more or less at the same time, the number of the former was, however, larger, and there was a more tolerant attitude toward them than to the Catholics, whose faith was imposed in Lithuanian territories fairly aggressively (↑).4Ирма Каплунайте, “Роль немецкого города в Вильнюсе во второй половине XIV в.”, Ukraina Lithuanica, 2017, т. IV, с. 125–126.

Iwo Jaworski has noted that the Ruthenian element – economically and culturally stronger – dominated over the Lithuanians, and Martseli Kosman even emphasized that Vilnius from the very beginning of its existence had a Ruthenian character.5Marceli Kosman, “Konflikty wyznaniowe w Wilnie (schyłek XVI–XVII w.)”, Kwartalnik Historyczny, r. 79, z. 1, 1972, s. 7. Adding to the ethnic diversity was the influence of German colonists, who appeared there at the time and with the support of Grand Duke Gediminas.6Iwo Jaworski, Zarys dziejów Wilna, Wilno: Wydawnictwo Magistratu m. Wilna, 1929, s. 4. Jews began coming to Vilnius in the 15th century; their number rapidly began to grow in the 16th century, and the city soon became the largest Jewish population center in the GDL. This complicated the language situation in the city during its development at the turn of the 16th to 17th centuries.7Jakub Niedźwiedź, Kultura literacka Wilna (1323–1655). Retoryczna organizacja miasta (series: Biblioteka Literatury Pogranicza, t. 20), Kraków: Towarzystwo Autorów i Wydawców Prac Naukowych Universitas, 2012, s. 37. Nevertheless, Vilnius gradually evolved on the model of a Polish medieval city. The evolution happened fairly slowly and was decisively set only in the first half of the 16th century. If it could be said that Vilnius in the 14th century was a Lithuanian-Ruthenian city, then in the 16th century it became Polish-Ruthenian in a cultural and linguistic sense.8Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 6.

In 1387, from the hands of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Wladyslaw II Jagiełło Vilnius received privilege for the Magdeburg law, which was fairly short and schematic.9Zbiór praw i przywilejów, miastu stolecznemu W.X.L. Wilnowi nadanych: Na żądanie wielu miast koronnych teź i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, wyd. P. Dubinski, Wilno, 1788, s. 1–2; M. Baliński, Historya miasta Wilna, t. 1, Wilno, 1836, s. 122. Also, it is not strange that, for practical needs, the city needed new documents. On 27 September 1432, Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis gave a new privileges for Vilnius, in which he confirmed for the city the Magdeburg law, all rights and privileges of the inhabitants of Vilnius, for both the Catholic and also the Ruthenian faith, and said that, in legal practices, the city should take example from Krakow. It is true that Iwo Jaworski considers that the practice of Polish cities would not always be useful for Lithuanian cities, and for Vilnius in particular, because there were other cultural and economic realities in the Polish cities, while the Lithuanian cities were, from the beginnings, multiethnic and multiconfessional.10Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 4. Inasmuch as the Orthodox population of the city had strong positions, it is not strange that, in the election for the magistrate’s office in 1533, a situation arose in which representatives of the Orthodox community held all the positions. At that time the Catholics of Vilnius, Poles, Germans, and Lithuanians who had been baptized in the Latin rite, lodged a complaint with King and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund І, who, reacting to this appeal, on 9 September 1536 proclaimed a new privilege, which was to regulate the conflict and keep order in the city.11Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 7. According to this, the city council of Vilnius was to be composed of 24 councilors and 12 burgomeisters, who were to be chosen in parity from representatives of the Roman and the Greek faiths. That is, there should be an equal number of Catholics and Orthodox in the Vilnius city council. Sigismund ІІІ Vasa confirmed this privilege on 9 June 1607. There was parity between Orthodox and Catholics in the 16th century in many Vilnius guilds.12Tomasz Kempa, “Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, David Frick, Ithaca–London 2013”: [review], Zapiski Historyczne, 2014, t. 79, z. 2, s. 135. For example, Sigismund August in the rule for the Vilnius shoemakers’ guild, published on 9 December 1552, ordered that in the guild six elders be elected annually, one half of whom should be of the Roman and the second half of the Greek faith.13Akty cechów wileńskich 1496–1759, cz. 1, wyd. M. i H. Łowmiańscy przy udziale S. Kościałkowskiego, Wilno: [s. n.], 1939, s. 45 (nr. 39). See also: Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 9–10. Similar rules were published in 1665 for the Vilnius tailors’ guild. In the statutes for the leatherworkers’ guild of 1672 it is foreseen that the guild should elect six elders – two persons each “of the Roman, Greek, and German faiths”.14David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 80. Representation in the College of 60 Men, a structure of civil society created in 1602, also was divided in two parts, “Greek” and “Roman”. In fact, it is most possible that representatives of various confessions could compete to participate in the work of this college.15David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 424.

A kind of parity was felt even in questions of calendar. The rhythm of life in Vilnius in the 17th century was determined by both the Julian and the Gregorian calendars; both functioned totally legally. On 29 July 1586, Stephen Bathory proclaimed for the people of Vilnius privileges according to which Orthodox craftsmen of the city should rest on Catholic religious holy days. This privilege did not give such weight to Orthodox holy days, though on 8 August of that year the king obliged the Vilnius magistrate not to force the Ruthenians to stand before city authorities on those holy days.16David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 79. As a consequence, there are no serious conflicts recorded which would have been provoked by the pressure of the Catholic community or the higher authorities regarding the use of the Julian calendar in religious practices of Orthodox or Protestants, as there was in some crown cities like Lviv.17David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 442. So it is not strange that the American researcher David Frick calls Vilnius “a city of many calendars” [2, 3, 4].18David Frick, “The Bells of Vilnius: Keeping Time in a City of Many Calendars”, in: Making Contact: Map, Identity, and Travel, eds. Glenn Burger, et al., Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press, 2003, р. 23. See also: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 77–81.

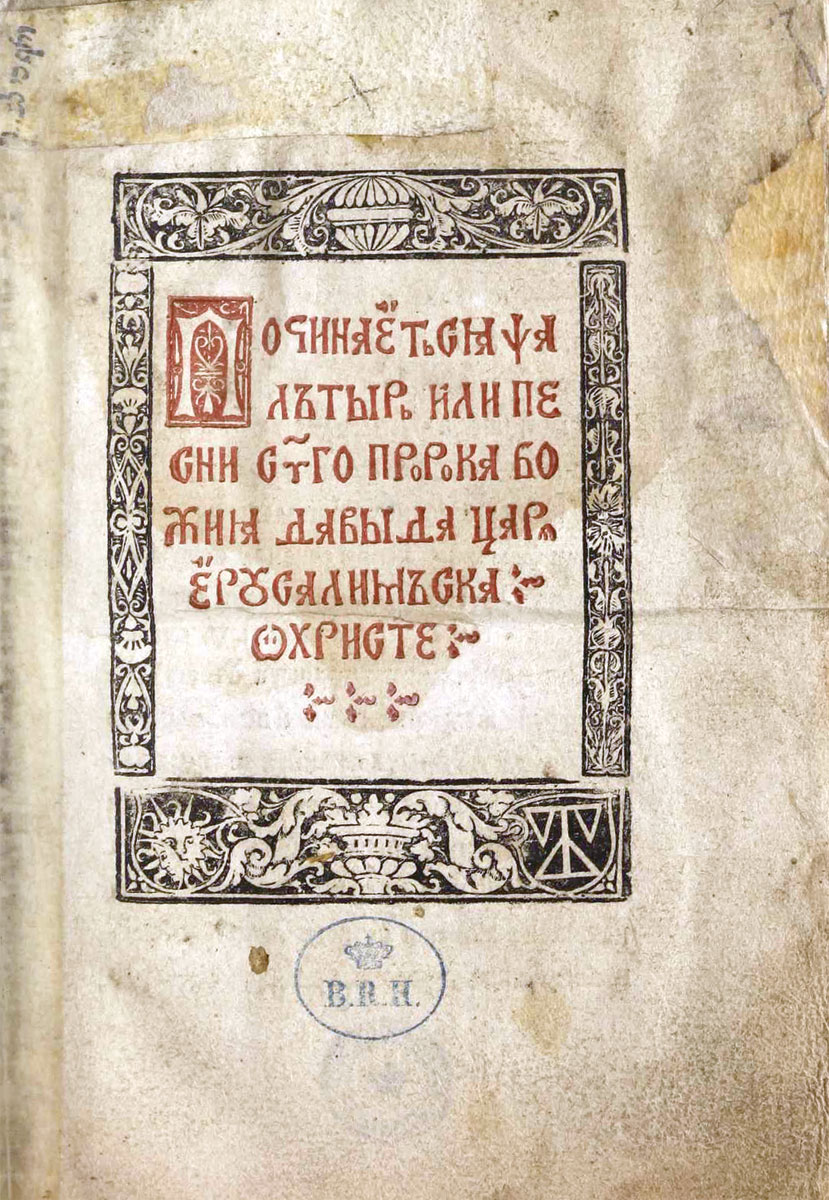

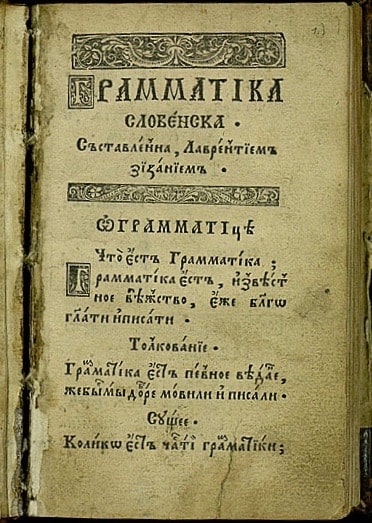

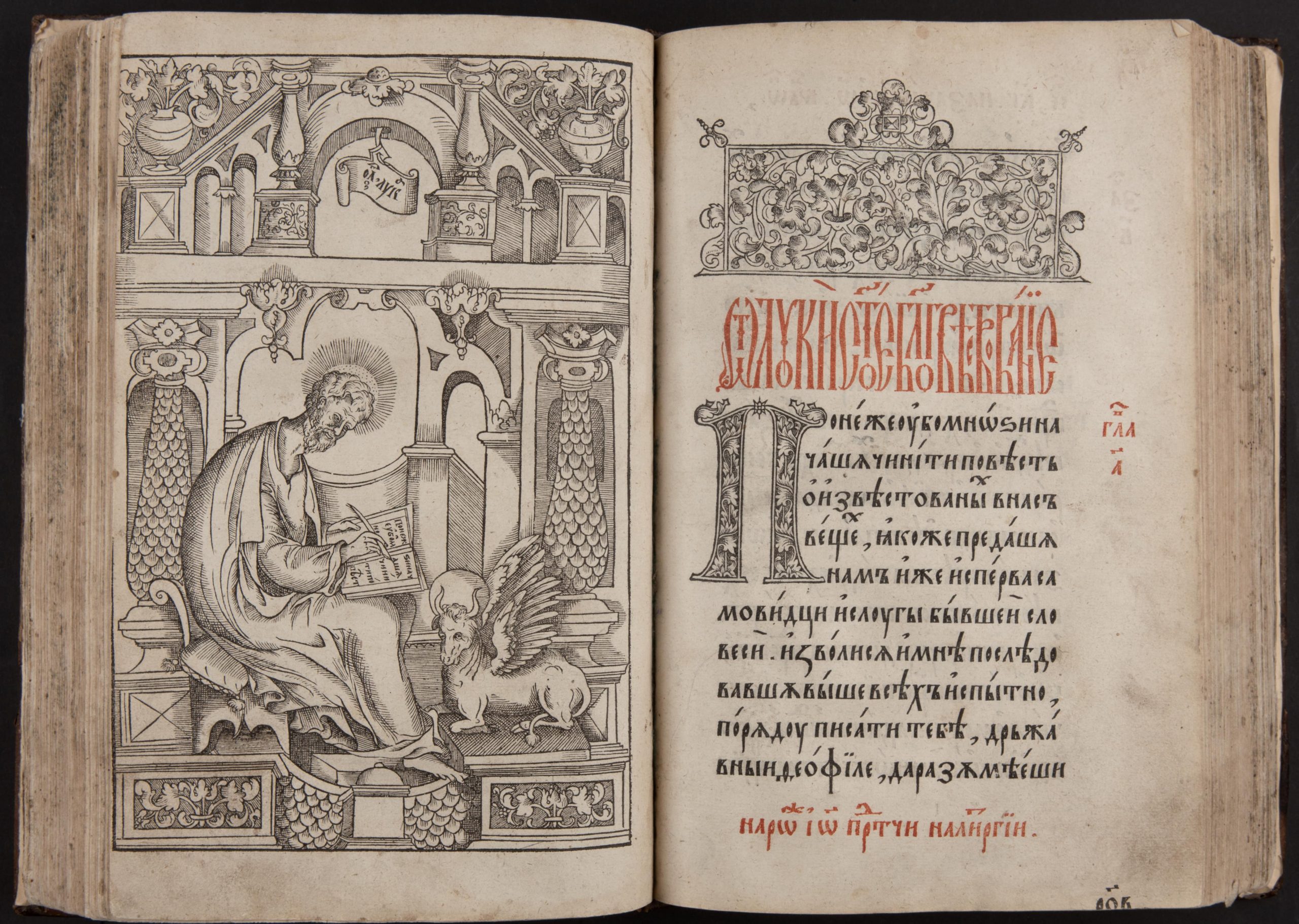

Orthodox Ruthenians constituted a considerable percentage of the population of the GDL.19Olena Rusyna provides date according to which in 1341 in the GDL the mainly Lithuanian lands were 1/2.5 the size of the Ruthenian lands, and already in 1430 they were about 1/12 the size. (Олена Русина, “Україна під татарами і Литвою”, Україна крізь віки, 1998, т. 6, с. 43). They brought with themselves literacy based on the Cyrillic alphabet and a language which for long years became a language of culture and an official language of the chancellery. The Ruthenian language was used at the state level in the GDL until 1696, and its status was guaranteed by the Lithuanian state. Inasmuch as a significant part of state institutions were concentrated in Vilnius, the Ruthenian element in the city was fairly significant for a long time. Already in the time of Vytautas, two categories of scribes worked in the chancellery of the Grand Duchy – Ruthenians, who wrote and edited Cyrillic texts, and also scribes who used Latin writing and edited not only Latin but also German-language documents. Among the 15 scribes in the chancellery of Duke Vytautas, one of the most known was Mykolai Tsybulska.20Jakub Niedźwiedź, op. cit., s. 227. In the 16th and 17th centuries, in some Lithuanian institutions like the nobles’ law court or the grand duke’s chancellery, as a rule they required the ability to communicate in a written language like Latin, also in Cyrillic letters, and also knowledge of a minimum of three languages: Ruthenian, Polish, and Latin.21Ibid., s. 228.

Only at the turn of the 17th century did the Ruthenian language give way to Polish. The language situation in Vilnius was not at all simple: in the 14th century, inhabitants of the city spoke in Lithuanian, Ruthenian, and partially in German, and from the end of the century Polish gradually faded from daily use. In the 15th century, the number of people who spoke in the Lithuanian language lessened, though they continued to play a significant role in communications in society. For example, even in 1634 in the refectory of the Vilnius University sermons for Lithuanians were preached in the Lithuanian language.22Ibid., s. 37. In the opinion of Jakub Niedźwiedź, in Vilnius “in the 16th and 17th centuries, the languages of daily communication (conversational) were, above all, Ruthenian (old Belarusian), and then Polish, Lithuanian, German, Yiddish, and Tatar. In the case of Tatar, linguistic assimilation happened quickly, and at the start of the 17th century they already spoke exclusively in Ruthenian and Polish.”23Ibid., s. 38. The American researcher David Frick has a slightly different opinion: he considers that already in the 17th century the Polish language predominated in the public sphere in Vilnius, that it had already by then become a kind of lingua franca, becoming the language of communication among various ethnic groups in the city.24According to the calculations of noted Polish historian Henryk Wisner, in the 17th century in Vilnius 53% of records in the city’s book of acts were written in the Polish language, 37% in Latin, and only 10% in the Ruthenian language. (Henryk Wisner, “The Reformation and National Culture: Lithuania”, Odrodzenie i Reformacja w Polsce, 2013, vol. 57, p. 98). Still, the author adds that Vilnius was distinguished by the use of various languages, and that it is sometimes difficult to establish the level of their spread, in particular among the lower classes. He supposes that in this environment a creole from the Polish and Lithuanian languages was spread, with the latter pre-dominating in the suburbs. Even in the 17th century, when the percentage of the use of the Polish language in various spheres of city life grew, the Ruthenian language continued to influence other languages that were then in use.25David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 114. See also: Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, „David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2013…“: [recenzija], Lithuanian Historical Studies, 2014, t. 19, p. 178.

In the 16th century, under the influence of strong Western cultural influences the Ruthenian community changed: it partly polonized. The city became not only a center of the Reformation in the GDL but of Calvinism. After 1666, when by the orders of Jan Casimir Vasa the “Roman” places in the Vilnius magistrate’s office were limited exclusively to Roman Catholics and the “Greek” ones to Uniates,26David Frick, „Five Confessions…“, p. 423–424. the Vilnius government elite was compromised of 60% Catholics and 40% Uniates. According to other data, at this time Poles made up approximately 50% of the population of Vilnius, Ruthenians approx. 30%, Germans approx. 8%, and Italians approx. 4%. The rest of the inhabitants were of Lithuanian, Hungarian, or Spanish background.27Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok: Wydawnictwo i Drukarnia Libra, 2015, s. 70, 72.

According to the Russian census of 1897, 31% of the inhabitants of Vilnius considered Polish their native language, 40% Yiddish, 20% Russian, 4,5% Belarusian, 1,5% German, and 2% Lithuanian.28Maria Barbara Topolska, “Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok, 2015…”: [review], Białostockie Teki Historyczne, 2017, t. 15, s. 280.

So, practically from the founding, the Ruthenian population predominated in Vilnius. In time, the positions of the Ruthenians changed, but throughout the centuries they remained an important component of the city’s cultural and political life.

The situation of the Ruthenian community in the GDL was regulated by a number of privileges of the years 1387, 1413, and 1432.

The level of urbanization in this area of Eastern Europe was insignificant. Only in the 16th century did the number of cities in Lithuania start to grow noticeably. Researchers reckon that there were approximately 220 urban centers in the country in the middle of this century. The largest and most famous was Vilnius, which was quickly growing and where, according to the calculations of researchers, 10 thousand people lived in the 16th century,2Paula Wydziałkowska, “Historia Wilna w XVI–XVIII wieku”, in: Koło Naukowe Muzealnictwa i Zabytkoznawstwa, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, available at: http://kolomuz.umk.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Paula-Wydzia%C5%82kowska-Historia-Wilna-w-XVI-XVIII-wieku.pdf, accessed: 2021 11 01; Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 19. and, at the end of the 17th century, the city and its suburbs numbered 20 thousand people3David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth Century Wilno, Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 2013, р. 7, 428. See also: David Frick, “Five Confessions in One City: Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern Wilno”, in: A Companion for Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern World (series: Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition, t. 28), ed. Tomas Max Saftey, Leiden: Brill, 2011, p. 422. [1].

Vilnius, which arose in the 13th and 14th centuries, was located on the border of two ethnic areas, Lithuanian and Ruthenian, which because of a number of circumstances were in the 14th century united within one state. Irma Kaplunaite writes that the Orthodox, the majority of whom were Ruthenians, settled on the territory of the future capital in the last quarter of the 13th century, during the rule of Traidenis, while the Catholics came to the city from the end of the 13th to the start of the 14th centuries. And, though Orthodox and Catholics settled in Vilnius more or less at the same time, the number of the former was, however, larger, and there was a more tolerant attitude toward them than to the Catholics, whose faith was imposed in Lithuanian territories fairly aggressively (↑).4Ирма Каплунайте, “Роль немецкого города в Вильнюсе во второй половине XIV в.”, Ukraina Lithuanica, 2017, т. IV, с. 125–126.

Iwo Jaworski has noted that the Ruthenian element – economically and culturally stronger – dominated over the Lithuanians, and Martseli Kosman even emphasized that Vilnius from the very beginning of its existence had a Ruthenian character.5Marceli Kosman, “Konflikty wyznaniowe w Wilnie (schyłek XVI–XVII w.)”, Kwartalnik Historyczny, r. 79, z. 1, 1972, s. 7. Adding to the ethnic diversity was the influence of German colonists, who appeared there at the time and with the support of Grand Duke Gediminas.6Iwo Jaworski, Zarys dziejów Wilna, Wilno: Wydawnictwo Magistratu m. Wilna, 1929, s. 4. Jews began coming to Vilnius in the 15th century; their number rapidly began to grow in the 16th century, and the city soon became the largest Jewish population center in the GDL. This complicated the language situation in the city during its development at the turn of the 16th to 17th centuries.7Jakub Niedźwiedź, Kultura literacka Wilna (1323–1655). Retoryczna organizacja miasta (series: Biblioteka Literatury Pogranicza, t. 20), Kraków: Towarzystwo Autorów i Wydawców Prac Naukowych Universitas, 2012, s. 37. Nevertheless, Vilnius gradually evolved on the model of a Polish medieval city. The evolution happened fairly slowly and was decisively set only in the first half of the 16th century. If it could be said that Vilnius in the 14th century was a Lithuanian-Ruthenian city, then in the 16th century it became Polish-Ruthenian in a cultural and linguistic sense.8Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 6.

In 1387, from the hands of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Wladyslaw II Jagiełło Vilnius received privilege for the Magdeburg law, which was fairly short and schematic.9Zbiór praw i przywilejów, miastu stolecznemu W.X.L. Wilnowi nadanych: Na żądanie wielu miast koronnych teź i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, wyd. P. Dubinski, Wilno, 1788, s. 1–2; M. Baliński, Historya miasta Wilna, t. 1, Wilno, 1836, s. 122. Also, it is not strange that, for practical needs, the city needed new documents. On 27 September 1432, Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis gave a new privileges for Vilnius, in which he confirmed for the city the Magdeburg law, all rights and privileges of the inhabitants of Vilnius, for both the Catholic and also the Ruthenian faith, and said that, in legal practices, the city should take example from Krakow. It is true that Iwo Jaworski considers that the practice of Polish cities would not always be useful for Lithuanian cities, and for Vilnius in particular, because there were other cultural and economic realities in the Polish cities, while the Lithuanian cities were, from the beginnings, multiethnic and multiconfessional.10Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 4. Inasmuch as the Orthodox population of the city had strong positions, it is not strange that, in the election for the magistrate’s office in 1533, a situation arose in which representatives of the Orthodox community held all the positions. At that time the Catholics of Vilnius, Poles, Germans, and Lithuanians who had been baptized in the Latin rite, lodged a complaint with King and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund І, who, reacting to this appeal, on 9 September 1536 proclaimed a new privilege, which was to regulate the conflict and keep order in the city.11Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 7. According to this, the city council of Vilnius was to be composed of 24 councilors and 12 burgomeisters, who were to be chosen in parity from representatives of the Roman and the Greek faiths. That is, there should be an equal number of Catholics and Orthodox in the Vilnius city council. Sigismund ІІІ Vasa confirmed this privilege on 9 June 1607. There was parity between Orthodox and Catholics in the 16th century in many Vilnius guilds.12Tomasz Kempa, “Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, David Frick, Ithaca–London 2013”: [review], Zapiski Historyczne, 2014, t. 79, z. 2, s. 135. For example, Sigismund August in the rule for the Vilnius shoemakers’ guild, published on 9 December 1552, ordered that in the guild six elders be elected annually, one half of whom should be of the Roman and the second half of the Greek faith.13Akty cechów wileńskich 1496–1759, cz. 1, wyd. M. i H. Łowmiańscy przy udziale S. Kościałkowskiego, Wilno: [s. n.], 1939, s. 45 (nr. 39). See also: Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 9–10. Similar rules were published in 1665 for the Vilnius tailors’ guild. In the statutes for the leatherworkers’ guild of 1672 it is foreseen that the guild should elect six elders – two persons each “of the Roman, Greek, and German faiths”.14David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 80. Representation in the College of 60 Men, a structure of civil society created in 1602, also was divided in two parts, “Greek” and “Roman”. In fact, it is most possible that representatives of various confessions could compete to participate in the work of this college.15David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 424.

A kind of parity was felt even in questions of calendar. The rhythm of life in Vilnius in the 17th century was determined by both the Julian and the Gregorian calendars; both functioned totally legally. On 29 July 1586, Stephen Bathory proclaimed for the people of Vilnius privileges according to which Orthodox craftsmen of the city should rest on Catholic religious holy days. This privilege did not give such weight to Orthodox holy days, though on 8 August of that year the king obliged the Vilnius magistrate not to force the Ruthenians to stand before city authorities on those holy days.16David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 79. As a consequence, there are no serious conflicts recorded which would have been provoked by the pressure of the Catholic community or the higher authorities regarding the use of the Julian calendar in religious practices of Orthodox or Protestants, as there was in some crown cities like Lviv.17David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 442. So it is not strange that the American researcher David Frick calls Vilnius “a city of many calendars” [2, 3, 4].18David Frick, “The Bells of Vilnius: Keeping Time in a City of Many Calendars”, in: Making Contact: Map, Identity, and Travel, eds. Glenn Burger, et al., Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press, 2003, р. 23. See also: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 77–81.

Orthodox Ruthenians constituted a considerable percentage of the population of the GDL.19Olena Rusyna provides date according to which in 1341 in the GDL the mainly Lithuanian lands were 1/2.5 the size of the Ruthenian lands, and already in 1430 they were about 1/12 the size. (Олена Русина, “Україна під татарами і Литвою”, Україна крізь віки, 1998, т. 6, с. 43). They brought with themselves literacy based on the Cyrillic alphabet and a language which for long years became a language of culture and an official language of the chancellery. The Ruthenian language was used at the state level in the GDL until 1696, and its status was guaranteed by the Lithuanian state. Inasmuch as a significant part of state institutions were concentrated in Vilnius, the Ruthenian element in the city was fairly significant for a long time. Already in the time of Vytautas, two categories of scribes worked in the chancellery of the Grand Duchy – Ruthenians, who wrote and edited Cyrillic texts, and also scribes who used Latin writing and edited not only Latin but also German-language documents. Among the 15 scribes in the chancellery of Duke Vytautas, one of the most known was Mykolai Tsybulska.20Jakub Niedźwiedź, op. cit., s. 227. In the 16th and 17th centuries, in some Lithuanian institutions like the nobles’ law court or the grand duke’s chancellery, as a rule they required the ability to communicate in a written language like Latin, also in Cyrillic letters, and also knowledge of a minimum of three languages: Ruthenian, Polish, and Latin.21Ibid., s. 228.

Only at the turn of the 17th century did the Ruthenian language give way to Polish. The language situation in Vilnius was not at all simple: in the 14th century, inhabitants of the city spoke in Lithuanian, Ruthenian, and partially in German, and from the end of the century Polish gradually faded from daily use. In the 15th century, the number of people who spoke in the Lithuanian language lessened, though they continued to play a significant role in communications in society. For example, even in 1634 in the refectory of the Vilnius University sermons for Lithuanians were preached in the Lithuanian language.22Ibid., s. 37. In the opinion of Jakub Niedźwiedź, in Vilnius “in the 16th and 17th centuries, the languages of daily communication (conversational) were, above all, Ruthenian (old Belarusian), and then Polish, Lithuanian, German, Yiddish, and Tatar. In the case of Tatar, linguistic assimilation happened quickly, and at the start of the 17th century they already spoke exclusively in Ruthenian and Polish.”23Ibid., s. 38. The American researcher David Frick has a slightly different opinion: he considers that already in the 17th century the Polish language predominated in the public sphere in Vilnius, that it had already by then become a kind of lingua franca, becoming the language of communication among various ethnic groups in the city.24According to the calculations of noted Polish historian Henryk Wisner, in the 17th century in Vilnius 53% of records in the city’s book of acts were written in the Polish language, 37% in Latin, and only 10% in the Ruthenian language. (Henryk Wisner, “The Reformation and National Culture: Lithuania”, Odrodzenie i Reformacja w Polsce, 2013, vol. 57, p. 98). Still, the author adds that Vilnius was distinguished by the use of various languages, and that it is sometimes difficult to establish the level of their spread, in particular among the lower classes. He supposes that in this environment a creole from the Polish and Lithuanian languages was spread, with the latter pre-dominating in the suburbs. Even in the 17th century, when the percentage of the use of the Polish language in various spheres of city life grew, the Ruthenian language continued to influence other languages that were then in use.25David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 114. See also: Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, „David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2013…“: [recenzija], Lithuanian Historical Studies, 2014, t. 19, p. 178.

In the 16th century, under the influence of strong Western cultural influences the Ruthenian community changed: it partly polonized. The city became not only a center of the Reformation in the GDL but of Calvinism. After 1666, when by the orders of Jan Casimir Vasa the “Roman” places in the Vilnius magistrate’s office were limited exclusively to Roman Catholics and the “Greek” ones to Uniates,26David Frick, „Five Confessions…“, p. 423–424. the Vilnius government elite was compromised of 60% Catholics and 40% Uniates. According to other data, at this time Poles made up approximately 50% of the population of Vilnius, Ruthenians approx. 30%, Germans approx. 8%, and Italians approx. 4%. The rest of the inhabitants were of Lithuanian, Hungarian, or Spanish background.27Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok: Wydawnictwo i Drukarnia Libra, 2015, s. 70, 72.

According to the Russian census of 1897, 31% of the inhabitants of Vilnius considered Polish their native language, 40% Yiddish, 20% Russian, 4,5% Belarusian, 1,5% German, and 2% Lithuanian.28Maria Barbara Topolska, “Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok, 2015…”: [review], Białostockie Teki Historyczne, 2017, t. 15, s. 280.

So, practically from the founding, the Ruthenian population predominated in Vilnius. In time, the positions of the Ruthenians changed, but throughout the centuries they remained an important component of the city’s cultural and political life.

Uniates in Vilnius

Vilnius from its beginnings was a multinational and multiconfessional city. As Irina Gerasimova correctly observed: “It is hardly possible to name any other European capital city of that time where five Christian confessions lived side by side – Orthodox, Uniates, Catholics, Calvinists, Lutherans, and also communities of Jews and Muslims. The sociocultural environment of this city, which is worthwhile understanding, like the co-existence of people who lived in one space but belonged to various religious confessions, ethne, and social levels, and had different goals, developed over the centuries, creating an unrepeatable atmosphere of the intertwining of various traditions, a culture of relationships, and art.”29Ирина Герасимова, Под властью русского царя: социокультурная среда Вильны в середине XVII века, Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2015, с. 7.

In the middle of the 16th century, during the Reformation, the confessional situation in the city became significantly more complicated. Significant communities of Lutherans and Calvinists were established here, and from 1596, with the signing of the Union of Brest, a split among the Orthodox occurred (↑).30See: Genutė Kirkienė, “Unijos idėja ir jos lietuviškoji recepcija”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 37–48; same: Генуте Кіркєнє, “Унійна ідея та її литовська рецепція”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 49–66. The supporters of church union, Uniates, with the support of the central as well as the city authorities, received certain advantages over the Orthodox, who had not accepted the conditions of union [5, 6, 7].31Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 135. Before the Union, the Orthodox community had approximately 20 monasteries and churches in the center of Vilnius. (The Roman Catholics had approx. 16.) Among these sacred buildings were the Cathedral of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God, the churches of the Orthodox Parish of Christ’s Resurrection, of the Lord’s Transfiguration, of St. John the Theologian, of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, of St. Paraskevia, the monastery churches of the Holy Trinity and of the Holy Spirit, and others.32Leonidas Timošenka, “Slavia Orthodoxa: atsinaujinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 57; same: Леонід Тимошенко, “Slavia Orthodoxa: криза й оновлення”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 82–83. Leonid Tymoshenko gives slightly different information in his monograph: “[…] Of the 16 Ruthenian churches, many were in the center of the city, close to no less than 16 Roman Catholic churches (the general amount of Latin parishes – 23) and two Protestant congregations” (Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 156). Leonid Tymoshenko entirely correctly noted that “the sacred space ‘Civitas Ruthenica’ in Vilnius essentially differed from the sociotopographic model of multiconfessional and typologically close Lviv, where the Ruthenian community had only one church in the city center, that of the Dormition Brotherhood” (↑).33Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 157.

After the signing of the union in 1596, the churches in Vilnius which belonged to the Orthodox were transferred to the Uniates. The Orthodox, instead, founded the new Monastery of the Holy Spirit, which became their main center.34David Frick, “Five Confessions…“, р. 421.

Consequently, already by the middle of the 17th century only one Orthodox church remained in Vilnius [8]. At this time, parishes of five Christian confessions operated in the city, in total 35 churches: 23 Roman Catholic, 9 Uniate, two Protestant.(Calvinist and Lutheran), and an Orthodox monastery. As a rule, hospitals and schools also operated at these parishes.35Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., р. 422. In addition, there was one synagogue and one mosque in Vilnius.

Because of the authorities’ protection of the Uniate community, there was a situational union of Orthodox and Protestants in the GDL. In May 1599, the Vilnius assembly of Orthodox and Protestants of the Duchy was held. It passed a decision to enact a league between them. The document was signed by 126 representatives of the Orthodox and Protestant nobility. However, this had no long-term consequences. Essentially, it was a short-term anti-Catholic confederation whose goal was to defend freedom of faith in the country through legal means (the principle of religious toleration, which was confirmed by an act of the Warsaw Confederation in 1573).36Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 156.

Still, there remained many supporters of the Union in Vilnius. Sometimes inhabitants accepted the Union as a consequence of religious toleration, a phenomenon inevitable in such a multicultural environment; sometimes opportunistic considerations served as the reason. This is not unusual, as the pressure on Orthodox and the attempts to incline them to the Union grew and became especially strong in the time of the rule of Sigismund III Vasa, and it was felt significantly stronger in the capital than in other Lithuanian cities.

The absence of clear boundaries between Uniates and Orthodox is demonstrated, in particular, by the support of the Orthodox of Holy Spirit Brotherhood for the Uniates in 1608–1609 in the conflict of the latter with Uniate Metropolitan of Kyiv Hipatius Pociej.37Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 134–135.

The history of the Uniates during the Muscovite occupation of Vilnius in 1655 could witness to a certain opportunism in the transfer from one confession to another. The question of the fate of the Uniates in Vilnius arose several times at various levels, but for some time they remained in the city. Only in June 1657 did the edict of Muscovite Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich regarding the deportation from the Lithuanian capital of all representatives of the Uniate community reach the city. But, since this was during a plague epidemic, and the majority of inhabitants had left the city, the execution of the edict did not succeed. Only in April 1658 was the question again placed on the order of the day. The Uniates either had to leave the city or return to Orthodoxy. Then the local governor (voivode) informed the tsar that the inhabitants of Vilnius accepted the idea of re-baptism fairly positively. As evidence, he provided a list of Uniate inhabitants who had agreed to transfer to the Orthodox faith. It had the names of representatives of 20 Vilnius families with servants. There was a separate list of names of women who lived without husbands and a few widows. The rite was to take place in the Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Spirit. Pope Alexander VII learned of the persecution of the Vilnius Uniates, and the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith was also informed of the situation. However, they advised the Vilnius Uniates to seek protection from Polish King Jan Casimir.38Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., с. 134–136. His help came together with the city’s liberation from Muscovite occupation.

In 1666, Jan Casimir Vasa promulgated privileges which corrected the privileges of Sigismund I regarding election of representatives of the Latin and Eastern rites to the Vilnius magistrat (municipal government) in equal portion. According to the new privileges, only Catholics and Uniates (the first on the “Roman” quota and the second on the “Greek”) should be chosen as burmisters (chairmen of the city council), councilors, and members of the city court. That is, Protestants and Orthodox had lost the opportunity to sit in the Vilnius magistrat.39David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 423–424. In a development of this decree, on 10 November 1673 at the request of Uniate Metropolitan Havryil Kolenda, King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki promulgated privileges in which the craft guilds of Vilnius were forbidden to elect Orthodox and Protestants as “annual elders”, and a violation of this command would be punished by a fine of 1000 Polish złotys.40Ibid., р. 425.

We see from a few preserved testaments of Vilnius inhabitants that the line between Orthodox and Uniates in Vilnius was movable. In the 17th century, only seven testaments of representatives of the Uniate community were noted in Vilnius municipal books. Five of them were composed in the 1660s, one dated to 1686, and the last to 1700.41Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris: Funeral Rituals and Civic Community in Seventeenth-century Vilnius: [master’s thesis], Central European University (Budapest), 2016, р. 45 Among the Uniate testators there were four men and three women: two of them – merchant Samuel Filipowicz (+1663) and burmister Jan Kukowicz (+1666) – state that they belonged to a brotherhood of Catholics of the Eastern rite, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which was created at Holy Trinity Church in 1622 (↑).

At that same time, 15 testaments of Orthodox inhabitants were recorded in the Vilnius book of acts, among which were the wills of women (6) and of men (9).42Ibid., р. 40.

A Uniate inhabitant of Vilnius, the wife of a merchant, Katerina Vasilevska (+1686), expressed her desire to be buried according to the custom of her community but not in the Orthodox cemetery next to her husband. Inhabitant Sofia Ignatovicz (+1700) wrote similarly in her testament: she asked to be buried in her family tomb near the Orthodox church, but the funeral should be celebrated according to the Uniate rite. Yet Uniate inhabitant of Vilnius Maria Semenovicz, a widow (+1667), requested in her will not only to be buried near an Orthodox church but also that Orthodox priests would pray for her soul.43Ibid., р. 47. In addition, three Uniate testators whose testaments are recorded in the city books asked to be buried near Holy Trinity Church.

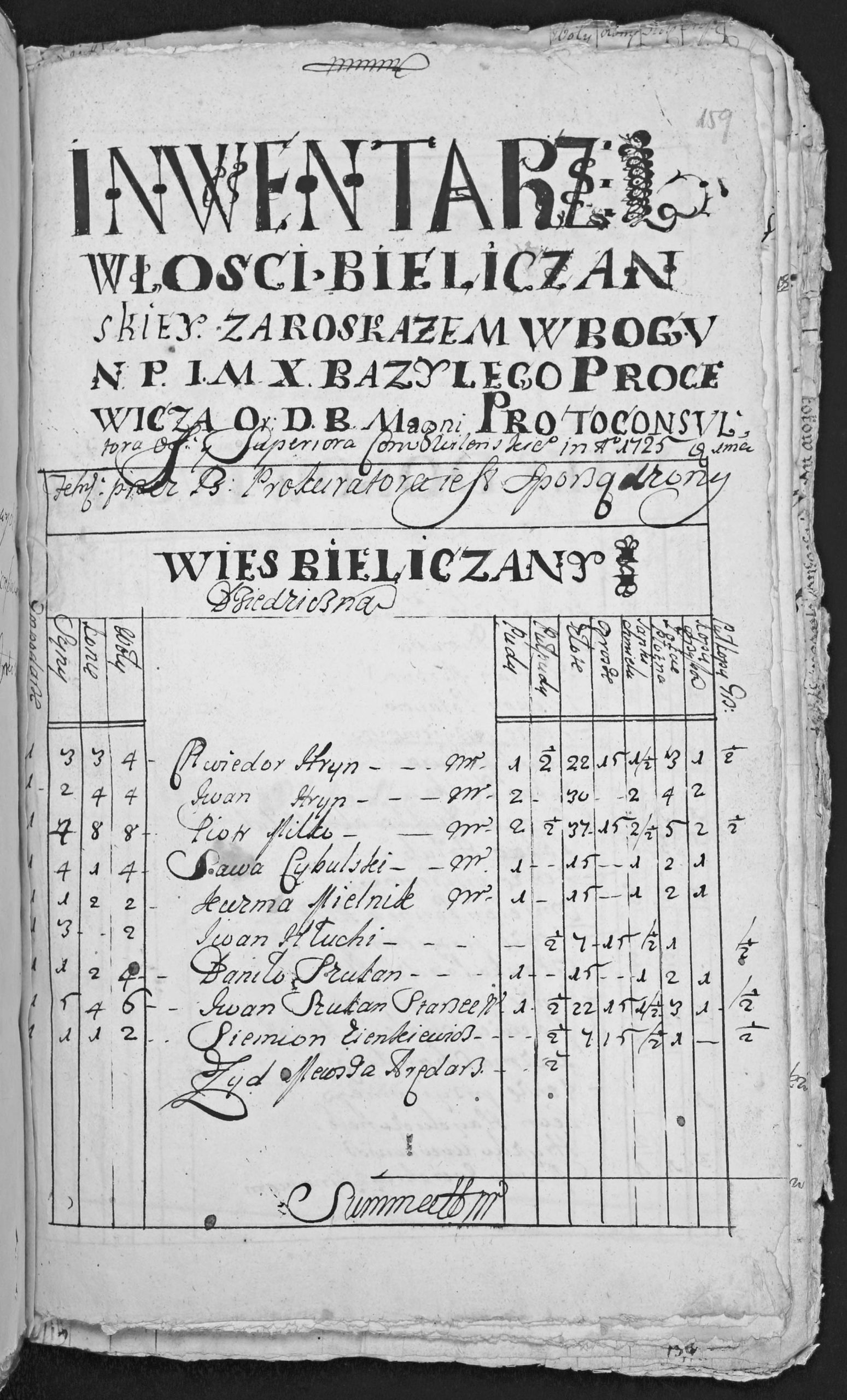

The boundaries between the Uniate and Orthodox communities were often conditional. This is demonstrated by the fact that in their wills Vilnius inhabitants of the Eastern rite often made donations to both Orthodox and Uniate monasteries. The previously mentioned Samuel Filipowicz in his testament left money to restore an icon of the Mother of God in Holy Trinity Church and asked Uniate priests to pray for his soul before the restored, exalted icon (↑). His testament also includes a request to the monks of Holy Spirit Monastery to pray for the repose of his soul, and for this he left the monastery a plot of land that was located near to it.44Ibid., р. 49. Samuel Boczoczka (1657), Kindrat Parfianowicz (1664), and others made such donations both for Orthodox and for Uniate churches.45See: Oksana Viničenko, “Rusėnų tapatybės, arba meldžiantis už sielas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 129–135; same: Оксана Вінниченко, “Монаші молитви за спасіння душ”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 201–204.

Oksana Vinnychenko noted that “initially some representatives of the ‘Greek Orthodox faith,’ following previous church tradition, designated funds for Trinity Monastery. However, from the second quarter of the 17th century the Basilian center was associated already exclusively with the Union, and laity who intentionally supported the Orthodox Church start to leave bequests only to benefit the monks of Holy Spirit.” [9, 10, 11] (↑) 46Ibid., p. 133; same: с. 202.

Analyzing the wills of Vilnius inhabitants of the 17th century, Povilas Dikavičius noted that the Uniates of Vilnius at that time had closer relations with the Orthodox than with representatives of other rites. The American David Frick came to a similar conclusion.47Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris…, р. 49; Wilnianie. Żywoty siedemnastowieczne (series: Bibliotheca Europae Orientalis, t. 32), оprac. David Frick, Warszawa: Przegląd Wschodni, 2008, s. XXII. He supposes that, since the Uniates came from the same cultural background as the Orthodox, contacts between these communities were rather close, and boundaries between them were for a long time fairly conditional, especially on an everyday level. Often, they did not consider questions of confessional allegiance when choosing godparents for children. Interconfessional marriages were spread in Vilnius; most often, the husband in the family was a Uniate and the wife Orthodox. David Frick explains such phenomena with the opportunistic thinking of inhabitants, especially when the issue is families which belong to the economic or social elite.48David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 212. This opinion seems quite plausible, especially in the context of changes which were introduced in the city in 1666.

At the turn of the 18th century, the development of the Uniate Church in the GDL related to the growth of the influence of Polish-Latin culture, though Uniates wanted to preserve their Ruthenian tradition. Uniate higher clergy functioned in the “sarmatian” realities of Commonwealth society, which could not fail to influence the development of the whole Uniate community [12, 13].49Andrzej Gil, Rusini w Rzeczypospolitej Wielu Narodów i ich obecność w tradycji Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego – problem historyczny czy czynnik tworzący współczesność?, available at: www.iesw.lublin.pl/projekty/pliki/IESW-121-02-07.pdf, accessed: 2020 05 05.

The introduction of the Union did not happen totally without clouds, and the sources report numerous conflicts, which involved the brothers of Holy Spirit Monastery, the Vilnius magistrat, Uniate bishops (↑) and archimandrites, simple inhabitants, etc. In particular, the Vilnius city books of 1601 contain a grievance of members of the Holy Spirit Brotherhood against the Vilnius magistrat, which summoned the confraternity to the king’s law court for review of their rights and privileges.50Акты, издаваемые Виленскою Археографическою комиссиею, т. 8: Акты Виленского гoродского суда, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1875, с. 60–61. In 1609, the city court considered the complaint of the Ruthenian part of the Vilnius magistrat against Uniate Archimandrite Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky (↑) regarding his illegal occupation of Holy Trinity Monastery,51Ibid., с. 77–78, 87. the protest of the Orthodox inhabitants of Vilnius on this occasion,52Ibid., с . 78, 80. and also the complaint of Rutsky himself against a landowner Szembel, regarding his statement of his desire to kill the archimandrite as an enemy of the Ruthenian faith.53Ibid., с . 80. The city books of 1629 contain the complaint of an elder of Holy Spirit Monastery in the name of all the brothers against Holy Trinity Monastery regarding an armed attack of their monks against nearby monks.54Ibid., с. 109. Practically every year there were a number of such complaints.

David Frick, showing the religious and confessional diversity in Vilnius, which a significant part of the inhabitants even in the time of the Counter-Reformation considered to be a good, leads the reader to the conclusion that we cannot speak of “tolerance” in the Lithuanian capital in the 17th century but only about “toleration” of people of other faiths.55See: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 411–418. And, as Gintautas Sliesoriūnas considers, it is worthwhile to agree with such an approach. Religious tolerance in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 16th and 17th centuries had its limits. In cities this rarely can relate to convictions, but more with the need to reconcile with the realities of fairly numerous communities which belonged to other confessions and had other religious rites.56Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, op. cit., p. 179.

In the 18th century, the single Orthodox monastery in Vilnius had only nine inhabitants. The Vilnius Tribunal was involved in the disputes of Orthodox with Catholics and Uniates at this time. After the Slutsk Confederation, in 1768 the Sejm constitution was approved, which guaranteed to the Orthodox freedom of worship, the press, and financial support of church leaders. However, the Catholic faith was determined as dominant in the state. In 1791 and 1792, separate commissions called which were to guarantee the implementation of this constitution, which demonstrates the resistance of the Catholic and Uniate hierarchies.57Maria Barbara Topolska, op. cit., s. 279. In time, the confessional situation in Vilnius changed. In 1791, the city had approximately 30 thousand inhabitants, among whom 60% were “Latins”, 35% Jews, 3% Protestants, and only 1% Uniates.58In the 19th century, the population of Vilnius quickly grew and, according to data of 1897, there were 154 532 persons, of which 63 986 were Jews (40%), 56 688 Catholics (approx. 37%), 28 638 Orthodox, 2 235 Lutherans, 1 318 Old Believers, and 842 Muslims. See: Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, op. cit., s. 97.

The Uniate Church in Lithuania was forbidden by the Russian authorities in 1839. At that moment, among the 36 thousand inhabitants of Vilnius, Catholics of the Eastern rite constituted slightly less than 3% (↑).59Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 20.

In the middle of the 16th century, during the Reformation, the confessional situation in the city became significantly more complicated. Significant communities of Lutherans and Calvinists were established here, and from 1596, with the signing of the Union of Brest, a split among the Orthodox occurred (↑).30See: Genutė Kirkienė, “Unijos idėja ir jos lietuviškoji recepcija”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 37–48; same: Генуте Кіркєнє, “Унійна ідея та її литовська рецепція”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 49–66. The supporters of church union, Uniates, with the support of the central as well as the city authorities, received certain advantages over the Orthodox, who had not accepted the conditions of union [5, 6, 7].31Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 135. Before the Union, the Orthodox community had approximately 20 monasteries and churches in the center of Vilnius. (The Roman Catholics had approx. 16.) Among these sacred buildings were the Cathedral of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God, the churches of the Orthodox Parish of Christ’s Resurrection, of the Lord’s Transfiguration, of St. John the Theologian, of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, of St. Paraskevia, the monastery churches of the Holy Trinity and of the Holy Spirit, and others.32Leonidas Timošenka, “Slavia Orthodoxa: atsinaujinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 57; same: Леонід Тимошенко, “Slavia Orthodoxa: криза й оновлення”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 82–83. Leonid Tymoshenko gives slightly different information in his monograph: “[…] Of the 16 Ruthenian churches, many were in the center of the city, close to no less than 16 Roman Catholic churches (the general amount of Latin parishes – 23) and two Protestant congregations” (Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 156). Leonid Tymoshenko entirely correctly noted that “the sacred space ‘Civitas Ruthenica’ in Vilnius essentially differed from the sociotopographic model of multiconfessional and typologically close Lviv, where the Ruthenian community had only one church in the city center, that of the Dormition Brotherhood” (↑).33Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 157.

After the signing of the union in 1596, the churches in Vilnius which belonged to the Orthodox were transferred to the Uniates. The Orthodox, instead, founded the new Monastery of the Holy Spirit, which became their main center.34David Frick, “Five Confessions…“, р. 421.

Consequently, already by the middle of the 17th century only one Orthodox church remained in Vilnius [8]. At this time, parishes of five Christian confessions operated in the city, in total 35 churches: 23 Roman Catholic, 9 Uniate, two Protestant.(Calvinist and Lutheran), and an Orthodox monastery. As a rule, hospitals and schools also operated at these parishes.35Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., р. 422. In addition, there was one synagogue and one mosque in Vilnius.

Because of the authorities’ protection of the Uniate community, there was a situational union of Orthodox and Protestants in the GDL. In May 1599, the Vilnius assembly of Orthodox and Protestants of the Duchy was held. It passed a decision to enact a league between them. The document was signed by 126 representatives of the Orthodox and Protestant nobility. However, this had no long-term consequences. Essentially, it was a short-term anti-Catholic confederation whose goal was to defend freedom of faith in the country through legal means (the principle of religious toleration, which was confirmed by an act of the Warsaw Confederation in 1573).36Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 156.

Still, there remained many supporters of the Union in Vilnius. Sometimes inhabitants accepted the Union as a consequence of religious toleration, a phenomenon inevitable in such a multicultural environment; sometimes opportunistic considerations served as the reason. This is not unusual, as the pressure on Orthodox and the attempts to incline them to the Union grew and became especially strong in the time of the rule of Sigismund III Vasa, and it was felt significantly stronger in the capital than in other Lithuanian cities.

The absence of clear boundaries between Uniates and Orthodox is demonstrated, in particular, by the support of the Orthodox of Holy Spirit Brotherhood for the Uniates in 1608–1609 in the conflict of the latter with Uniate Metropolitan of Kyiv Hipatius Pociej.37Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 134–135.

The history of the Uniates during the Muscovite occupation of Vilnius in 1655 could witness to a certain opportunism in the transfer from one confession to another. The question of the fate of the Uniates in Vilnius arose several times at various levels, but for some time they remained in the city. Only in June 1657 did the edict of Muscovite Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich regarding the deportation from the Lithuanian capital of all representatives of the Uniate community reach the city. But, since this was during a plague epidemic, and the majority of inhabitants had left the city, the execution of the edict did not succeed. Only in April 1658 was the question again placed on the order of the day. The Uniates either had to leave the city or return to Orthodoxy. Then the local governor (voivode) informed the tsar that the inhabitants of Vilnius accepted the idea of re-baptism fairly positively. As evidence, he provided a list of Uniate inhabitants who had agreed to transfer to the Orthodox faith. It had the names of representatives of 20 Vilnius families with servants. There was a separate list of names of women who lived without husbands and a few widows. The rite was to take place in the Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Spirit. Pope Alexander VII learned of the persecution of the Vilnius Uniates, and the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith was also informed of the situation. However, they advised the Vilnius Uniates to seek protection from Polish King Jan Casimir.38Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., с. 134–136. His help came together with the city’s liberation from Muscovite occupation.

In 1666, Jan Casimir Vasa promulgated privileges which corrected the privileges of Sigismund I regarding election of representatives of the Latin and Eastern rites to the Vilnius magistrat (municipal government) in equal portion. According to the new privileges, only Catholics and Uniates (the first on the “Roman” quota and the second on the “Greek”) should be chosen as burmisters (chairmen of the city council), councilors, and members of the city court. That is, Protestants and Orthodox had lost the opportunity to sit in the Vilnius magistrat.39David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 423–424. In a development of this decree, on 10 November 1673 at the request of Uniate Metropolitan Havryil Kolenda, King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki promulgated privileges in which the craft guilds of Vilnius were forbidden to elect Orthodox and Protestants as “annual elders”, and a violation of this command would be punished by a fine of 1000 Polish złotys.40Ibid., р. 425.

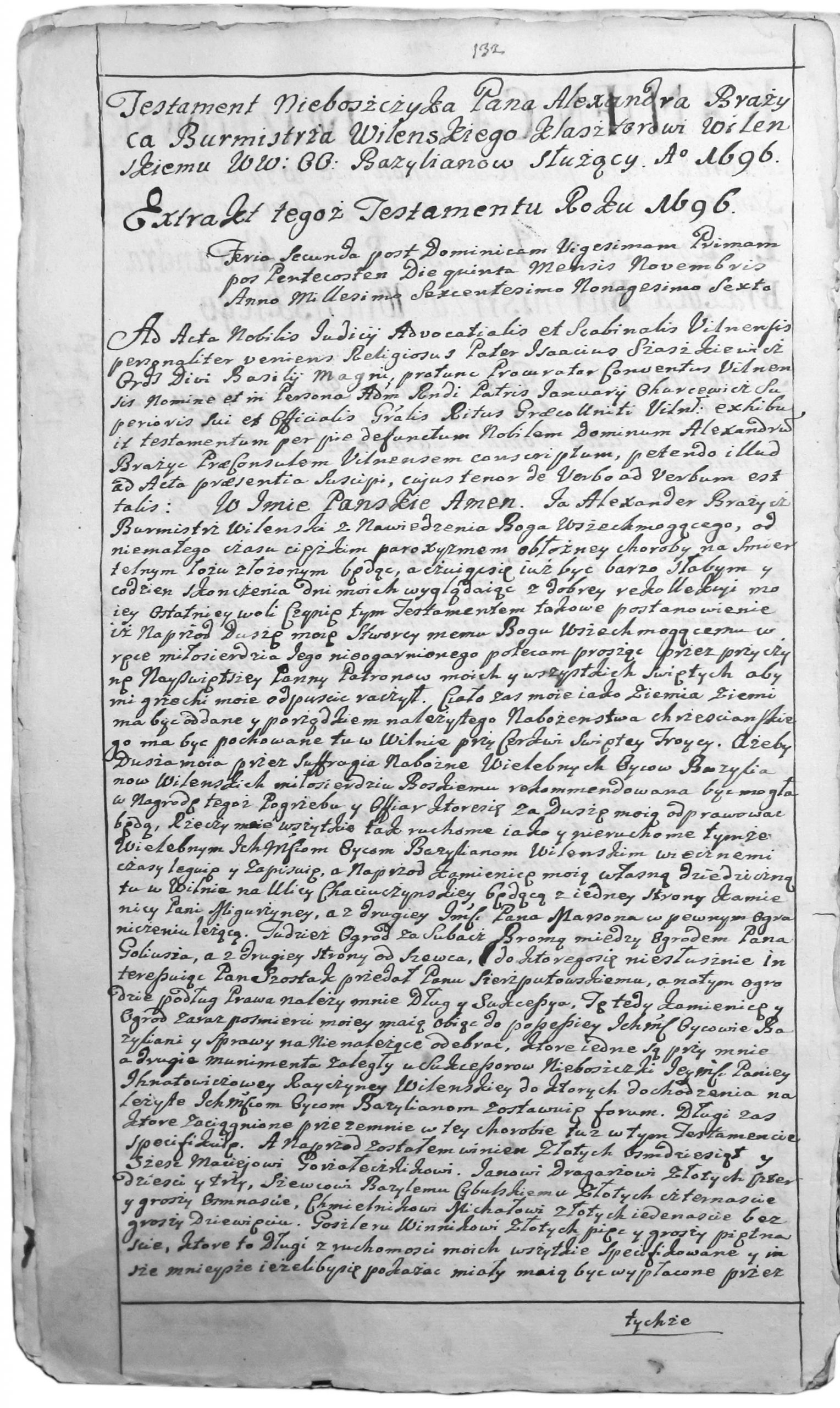

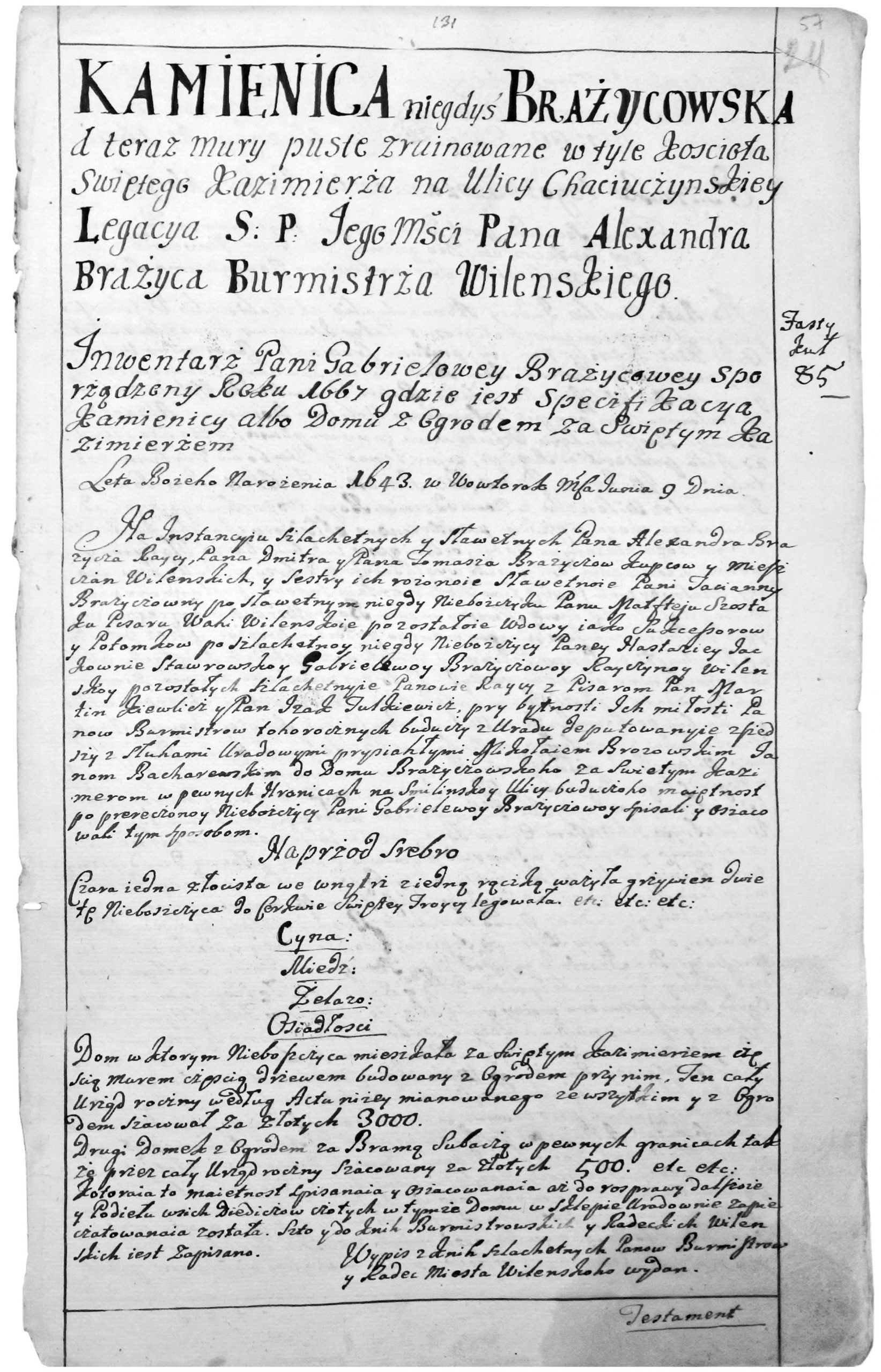

We see from a few preserved testaments of Vilnius inhabitants that the line between Orthodox and Uniates in Vilnius was movable. In the 17th century, only seven testaments of representatives of the Uniate community were noted in Vilnius municipal books. Five of them were composed in the 1660s, one dated to 1686, and the last to 1700.41Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris: Funeral Rituals and Civic Community in Seventeenth-century Vilnius: [master’s thesis], Central European University (Budapest), 2016, р. 45 Among the Uniate testators there were four men and three women: two of them – merchant Samuel Filipowicz (+1663) and burmister Jan Kukowicz (+1666) – state that they belonged to a brotherhood of Catholics of the Eastern rite, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which was created at Holy Trinity Church in 1622 (↑).

At that same time, 15 testaments of Orthodox inhabitants were recorded in the Vilnius book of acts, among which were the wills of women (6) and of men (9).42Ibid., р. 40.

A Uniate inhabitant of Vilnius, the wife of a merchant, Katerina Vasilevska (+1686), expressed her desire to be buried according to the custom of her community but not in the Orthodox cemetery next to her husband. Inhabitant Sofia Ignatovicz (+1700) wrote similarly in her testament: she asked to be buried in her family tomb near the Orthodox church, but the funeral should be celebrated according to the Uniate rite. Yet Uniate inhabitant of Vilnius Maria Semenovicz, a widow (+1667), requested in her will not only to be buried near an Orthodox church but also that Orthodox priests would pray for her soul.43Ibid., р. 47. In addition, three Uniate testators whose testaments are recorded in the city books asked to be buried near Holy Trinity Church.

The boundaries between the Uniate and Orthodox communities were often conditional. This is demonstrated by the fact that in their wills Vilnius inhabitants of the Eastern rite often made donations to both Orthodox and Uniate monasteries. The previously mentioned Samuel Filipowicz in his testament left money to restore an icon of the Mother of God in Holy Trinity Church and asked Uniate priests to pray for his soul before the restored, exalted icon (↑). His testament also includes a request to the monks of Holy Spirit Monastery to pray for the repose of his soul, and for this he left the monastery a plot of land that was located near to it.44Ibid., р. 49. Samuel Boczoczka (1657), Kindrat Parfianowicz (1664), and others made such donations both for Orthodox and for Uniate churches.45See: Oksana Viničenko, “Rusėnų tapatybės, arba meldžiantis už sielas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 129–135; same: Оксана Вінниченко, “Монаші молитви за спасіння душ”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 201–204.

Oksana Vinnychenko noted that “initially some representatives of the ‘Greek Orthodox faith,’ following previous church tradition, designated funds for Trinity Monastery. However, from the second quarter of the 17th century the Basilian center was associated already exclusively with the Union, and laity who intentionally supported the Orthodox Church start to leave bequests only to benefit the monks of Holy Spirit.” [9, 10, 11] (↑) 46Ibid., p. 133; same: с. 202.

Analyzing the wills of Vilnius inhabitants of the 17th century, Povilas Dikavičius noted that the Uniates of Vilnius at that time had closer relations with the Orthodox than with representatives of other rites. The American David Frick came to a similar conclusion.47Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris…, р. 49; Wilnianie. Żywoty siedemnastowieczne (series: Bibliotheca Europae Orientalis, t. 32), оprac. David Frick, Warszawa: Przegląd Wschodni, 2008, s. XXII. He supposes that, since the Uniates came from the same cultural background as the Orthodox, contacts between these communities were rather close, and boundaries between them were for a long time fairly conditional, especially on an everyday level. Often, they did not consider questions of confessional allegiance when choosing godparents for children. Interconfessional marriages were spread in Vilnius; most often, the husband in the family was a Uniate and the wife Orthodox. David Frick explains such phenomena with the opportunistic thinking of inhabitants, especially when the issue is families which belong to the economic or social elite.48David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 212. This opinion seems quite plausible, especially in the context of changes which were introduced in the city in 1666.

At the turn of the 18th century, the development of the Uniate Church in the GDL related to the growth of the influence of Polish-Latin culture, though Uniates wanted to preserve their Ruthenian tradition. Uniate higher clergy functioned in the “sarmatian” realities of Commonwealth society, which could not fail to influence the development of the whole Uniate community [12, 13].49Andrzej Gil, Rusini w Rzeczypospolitej Wielu Narodów i ich obecność w tradycji Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego – problem historyczny czy czynnik tworzący współczesność?, available at: www.iesw.lublin.pl/projekty/pliki/IESW-121-02-07.pdf, accessed: 2020 05 05.

The introduction of the Union did not happen totally without clouds, and the sources report numerous conflicts, which involved the brothers of Holy Spirit Monastery, the Vilnius magistrat, Uniate bishops (↑) and archimandrites, simple inhabitants, etc. In particular, the Vilnius city books of 1601 contain a grievance of members of the Holy Spirit Brotherhood against the Vilnius magistrat, which summoned the confraternity to the king’s law court for review of their rights and privileges.50Акты, издаваемые Виленскою Археографическою комиссиею, т. 8: Акты Виленского гoродского суда, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1875, с. 60–61. In 1609, the city court considered the complaint of the Ruthenian part of the Vilnius magistrat against Uniate Archimandrite Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky (↑) regarding his illegal occupation of Holy Trinity Monastery,51Ibid., с. 77–78, 87. the protest of the Orthodox inhabitants of Vilnius on this occasion,52Ibid., с . 78, 80. and also the complaint of Rutsky himself against a landowner Szembel, regarding his statement of his desire to kill the archimandrite as an enemy of the Ruthenian faith.53Ibid., с . 80. The city books of 1629 contain the complaint of an elder of Holy Spirit Monastery in the name of all the brothers against Holy Trinity Monastery regarding an armed attack of their monks against nearby monks.54Ibid., с. 109. Practically every year there were a number of such complaints.

David Frick, showing the religious and confessional diversity in Vilnius, which a significant part of the inhabitants even in the time of the Counter-Reformation considered to be a good, leads the reader to the conclusion that we cannot speak of “tolerance” in the Lithuanian capital in the 17th century but only about “toleration” of people of other faiths.55See: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 411–418. And, as Gintautas Sliesoriūnas considers, it is worthwhile to agree with such an approach. Religious tolerance in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 16th and 17th centuries had its limits. In cities this rarely can relate to convictions, but more with the need to reconcile with the realities of fairly numerous communities which belonged to other confessions and had other religious rites.56Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, op. cit., p. 179.

In the 18th century, the single Orthodox monastery in Vilnius had only nine inhabitants. The Vilnius Tribunal was involved in the disputes of Orthodox with Catholics and Uniates at this time. After the Slutsk Confederation, in 1768 the Sejm constitution was approved, which guaranteed to the Orthodox freedom of worship, the press, and financial support of church leaders. However, the Catholic faith was determined as dominant in the state. In 1791 and 1792, separate commissions called which were to guarantee the implementation of this constitution, which demonstrates the resistance of the Catholic and Uniate hierarchies.57Maria Barbara Topolska, op. cit., s. 279. In time, the confessional situation in Vilnius changed. In 1791, the city had approximately 30 thousand inhabitants, among whom 60% were “Latins”, 35% Jews, 3% Protestants, and only 1% Uniates.58In the 19th century, the population of Vilnius quickly grew and, according to data of 1897, there were 154 532 persons, of which 63 986 were Jews (40%), 56 688 Catholics (approx. 37%), 28 638 Orthodox, 2 235 Lutherans, 1 318 Old Believers, and 842 Muslims. See: Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, op. cit., s. 97.

The Uniate Church in Lithuania was forbidden by the Russian authorities in 1839. At that moment, among the 36 thousand inhabitants of Vilnius, Catholics of the Eastern rite constituted slightly less than 3% (↑).59Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 20.

Tetiana Hoshko

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | See: Aleksander Krawcewicz, “Stosunki religijne w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XIII wieku i początkach XIV stulecia”, in: Między Rusią a Polską Litwa. Od Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego do Republiki Litewskiej, pod red. Jerzegy Grzybowski, Joanna Kozłowska, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2015, s. 41–48. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Paula Wydziałkowska, “Historia Wilna w XVI–XVIII wieku”, in: Koło Naukowe Muzealnictwa i Zabytkoznawstwa, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, available at: http://kolomuz.umk.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Paula-Wydzia%C5%82kowska-Historia-Wilna-w-XVI-XVIII-wieku.pdf, accessed: 2021 11 01; Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 19. |

| 3. | ↑ | David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth Century Wilno, Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 2013, р. 7, 428. See also: David Frick, “Five Confessions in One City: Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern Wilno”, in: A Companion for Multiconfessionalism in Early Modern World (series: Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition, t. 28), ed. Tomas Max Saftey, Leiden: Brill, 2011, p. 422. |

| 4. | ↑ | Ирма Каплунайте, “Роль немецкого города в Вильнюсе во второй половине XIV в.”, Ukraina Lithuanica, 2017, т. IV, с. 125–126. |

| 5. | ↑ | Marceli Kosman, “Konflikty wyznaniowe w Wilnie (schyłek XVI–XVII w.)”, Kwartalnik Historyczny, r. 79, z. 1, 1972, s. 7. |

| 6. | ↑ | Iwo Jaworski, Zarys dziejów Wilna, Wilno: Wydawnictwo Magistratu m. Wilna, 1929, s. 4. |

| 7. | ↑ | Jakub Niedźwiedź, Kultura literacka Wilna (1323–1655). Retoryczna organizacja miasta (series: Biblioteka Literatury Pogranicza, t. 20), Kraków: Towarzystwo Autorów i Wydawców Prac Naukowych Universitas, 2012, s. 37. |

| 8. | ↑ | Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 6. |

| 9. | ↑ | Zbiór praw i przywilejów, miastu stolecznemu W.X.L. Wilnowi nadanych: Na żądanie wielu miast koronnych teź i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, wyd. P. Dubinski, Wilno, 1788, s. 1–2; M. Baliński, Historya miasta Wilna, t. 1, Wilno, 1836, s. 122. |

| 10. | ↑ | Iwo Jaworski, op. cit., s. 4. |

| 11. | ↑ | Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 7. |

| 12. | ↑ | Tomasz Kempa, “Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, David Frick, Ithaca–London 2013”: [review], Zapiski Historyczne, 2014, t. 79, z. 2, s. 135. |

| 13. | ↑ | Akty cechów wileńskich 1496–1759, cz. 1, wyd. M. i H. Łowmiańscy przy udziale S. Kościałkowskiego, Wilno: [s. n.], 1939, s. 45 (nr. 39). See also: Marceli Kosman, op. cit., s. 9–10. |

| 14. | ↑ | David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 80. |

| 15. | ↑ | David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 424. |

| 16. | ↑ | David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 79. |

| 17. | ↑ | David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 442. |

| 18. | ↑ | David Frick, “The Bells of Vilnius: Keeping Time in a City of Many Calendars”, in: Making Contact: Map, Identity, and Travel, eds. Glenn Burger, et al., Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press, 2003, р. 23. See also: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 77–81. |

| 19. | ↑ | Olena Rusyna provides date according to which in 1341 in the GDL the mainly Lithuanian lands were 1/2.5 the size of the Ruthenian lands, and already in 1430 they were about 1/12 the size. (Олена Русина, “Україна під татарами і Литвою”, Україна крізь віки, 1998, т. 6, с. 43). |

| 20. | ↑ | Jakub Niedźwiedź, op. cit., s. 227. |

| 21. | ↑ | Ibid., s. 228. |

| 22. | ↑ | Ibid., s. 37. |

| 23. | ↑ | Ibid., s. 38. |

| 24. | ↑ | According to the calculations of noted Polish historian Henryk Wisner, in the 17th century in Vilnius 53% of records in the city’s book of acts were written in the Polish language, 37% in Latin, and only 10% in the Ruthenian language. (Henryk Wisner, “The Reformation and National Culture: Lithuania”, Odrodzenie i Reformacja w Polsce, 2013, vol. 57, p. 98). |

| 25. | ↑ | David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 114. See also: Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, „David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2013…“: [recenzija], Lithuanian Historical Studies, 2014, t. 19, p. 178. |

| 26. | ↑ | David Frick, „Five Confessions…“, p. 423–424. |

| 27. | ↑ | Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok: Wydawnictwo i Drukarnia Libra, 2015, s. 70, 72. |

| 28. | ↑ | Maria Barbara Topolska, “Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto wielu religii i narodów, Białystok, 2015…”: [review], Białostockie Teki Historyczne, 2017, t. 15, s. 280. |

| 29. | ↑ | Ирина Герасимова, Под властью русского царя: социокультурная среда Вильны в середине XVII века, Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2015, с. 7. |

| 30. | ↑ | See: Genutė Kirkienė, “Unijos idėja ir jos lietuviškoji recepcija”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 37–48; same: Генуте Кіркєнє, “Унійна ідея та її литовська рецепція”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 49–66. |

| 31. | ↑ | Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 135. |

| 32. | ↑ | Leonidas Timošenka, “Slavia Orthodoxa: atsinaujinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 57; same: Леонід Тимошенко, “Slavia Orthodoxa: криза й оновлення”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 82–83. Leonid Tymoshenko gives slightly different information in his monograph: “[…] Of the 16 Ruthenian churches, many were in the center of the city, close to no less than 16 Roman Catholic churches (the general amount of Latin parishes – 23) and two Protestant congregations” (Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 156). |

| 33. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 157. |

| 34. | ↑ | David Frick, “Five Confessions…“, р. 421. |

| 35. | ↑ | Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., р. 422. In addition, there was one synagogue and one mosque in Vilnius. |

| 36. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура…, с. 156. |

| 37. | ↑ | Tomasz Kempa, op. cit., s. 134–135. |

| 38. | ↑ | Ирина Герасимова, op. cit., с. 134–136. |

| 39. | ↑ | David Frick, “Five Confessions…”, p. 423–424. |

| 40. | ↑ | Ibid., р. 425. |

| 41. | ↑ | Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris: Funeral Rituals and Civic Community in Seventeenth-century Vilnius: [master’s thesis], Central European University (Budapest), 2016, р. 45 |

| 42. | ↑ | Ibid., р. 40. |

| 43. | ↑ | Ibid., р. 47. |

| 44. | ↑ | Ibid., р. 49. |

| 45. | ↑ | See: Oksana Viničenko, “Rusėnų tapatybės, arba meldžiantis už sielas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 129–135; same: Оксана Вінниченко, “Монаші молитви за спасіння душ”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 201–204. |

| 46. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 133; same: с. 202. |

| 47. | ↑ | Povilas Dikavičius, Pompa Funebris…, р. 49; Wilnianie. Żywoty siedemnastowieczne (series: Bibliotheca Europae Orientalis, t. 32), оprac. David Frick, Warszawa: Przegląd Wschodni, 2008, s. XXII. |

| 48. | ↑ | David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, p. 212. |

| 49. | ↑ | Andrzej Gil, Rusini w Rzeczypospolitej Wielu Narodów i ich obecność w tradycji Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego – problem historyczny czy czynnik tworzący współczesność?, available at: www.iesw.lublin.pl/projekty/pliki/IESW-121-02-07.pdf, accessed: 2020 05 05. |

| 50. | ↑ | Акты, издаваемые Виленскою Археографическою комиссиею, т. 8: Акты Виленского гoродского суда, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1875, с. 60–61. |

| 51. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 77–78, 87. |

| 52. | ↑ | Ibid., с . 78, 80. |

| 53. | ↑ | Ibid., с . 80. |

| 54. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 109. |

| 55. | ↑ | See: David Frick, Kith, Kin, and Neighbors…, р. 411–418. |

| 56. | ↑ | Gintautas Sliesoriūnas, op. cit., p. 179. |

| 57. | ↑ | Maria Barbara Topolska, op. cit., s. 279. |

| 58. | ↑ | In the 19th century, the population of Vilnius quickly grew and, according to data of 1897, there were 154 532 persons, of which 63 986 were Jews (40%), 56 688 Catholics (approx. 37%), 28 638 Orthodox, 2 235 Lutherans, 1 318 Old Believers, and 842 Muslims. See: Urszula Anna Pawluczuk, op. cit., s. 97. |

| 59. | ↑ | Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 15; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Монаша спільнота Василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 20. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Published in: Vladas Drėma, Dingęs Vilnius = Lost Vilnius = Исчезнувший Вильнюс , Vilnius: Блюмовича, 1991, p. 34–35 (il. 27). |

| 2. | Малая подорожная книжка…, [Vilnius: Press of Francysk Skaryna, 1522], p. [title page of the Psalter]. Held in: Det Kongelige Bibliotek. Published in: “Pranciškaus Skorinos Rusėniškajai Biblijai – 500:: [virtual exhibit], in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka, 2017, available at: http://web1.mab.lt/skorina/portfolio/skorina-ir-lietuva/kb-mazoji-kk-psalmyno-ant, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 3. | Лаврентий Зизаний, Грамматика словенска…, [Vilnius, 1596], p. [А]1. Published in: “Граматика словенська. Лексис”, in: Internet Archive, 2018, available at: https://archive.org/details/gramat0slovenska/mode/2up, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 4. | Евангелие…, Вильнo: Петр Тимофеев Мстиславец, 1575, p. [St. Luke the Apostle and the beginning of the Gospel]. Held in: VUB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, Rk54. Published in: “Pranciškaus Skorinos Rusėniškajai Biblijai – 500”: [virtual exhibit], in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka, 2017, available at: http://web1.mab.lt/skorina/portfolio/po-skorinos/vub-sv-apast, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 5. | From a panegyric of the superior (archimandrite) of Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius and Priest Aleksy Dubowicz to the voievod [governor] of Vilnius, Janusz Skumin-Tyszkewicz (published at the Press of Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius, 1642). Published in: Гісторыя беларускай кнігі, т. 1: Кніжная культура Вялікага Княства Літоўскага, ред. М. B. Нікалаеў, Менск: Беларуская энцыклапедыя імя Петруся Броўкі, 2009, с. 199. |

| 6. | Held in: LNM, LNM T 1032. |

| 7. | Held in: BN, G.55/Sz.6 (Available at: Polona, https://polona.pl/item/perillustri-r-everen-d-issm-o-d-omi-no-josaphat-brazyc-patroni-iosaphat-sancti,NzI3MjQw/0/#info:metadata, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 8. | Памятники русской старины в западных губерниях империи, т. 5: Вильна: [album], St. Petersburg: [М-во внутр. дел Ministry of Internal Affairs], 1870, ил. 14. Held in: LNDM, LNDM G 4523 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/detali-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000005846607?s_id=0GX9p8a33pUbgPnU&s_ind=17&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 9. | Held in: ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 426-а, арк. 57. |

| 10. | Held in: Ibid., арк. 56. |

| 11. | Held in: НМЛ, Відділ рукописної та стародрукованої книги, Ркл-581, арк. 84. |

| 12. | Held in: Ibid., арк. 46. |

| 13. | [Jan Olszewski], Obrona monastyra Wileńskiego cerkwi Przenayświętszey Troycy, y zupełna informacya przez wielebnych oo. bazylianow wileńskich unitów przy teyże cerkwi zostających…, Wilno, 1702, p. [title page]. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, f. L-18, b. 2-44, l. 1. |