In a handbook for novices of the Basilian Order from the 18th century, it confirms that “the task of a monk is to communicate with God through prayer, meditation, and reading devout books”.1Pietro Menniti, Szkoła bazylianska zamykająca nauki dla dobrego wychowania nowiciuszow i professow Z.S. Bazylego W., Wilno: W drukarni J. K. M. XX. Bazylianow, 1764, s. 251. It also explains when and how those who have devoted their lives to God should use a book. One of the important teachings during the formation of a novice is that, without a book, it is impossible to become a good monk.

The importance of the written word on the spiritual path of a Basilian influenced the significance of the monastic library. When the Basilian Order was founded in 1617, Protoarchimandrite Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky (↑), relying on the experience of the Society of Jesus, compiled the rules of the librarian. Already in this document the structure of an exemplary Basilian library was formulated: secular literature separated from religious, and the latter was separated in two sections – of the Greek and Latin.2Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пьєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік = Bazyliańskie kapituły generalne od 1617 do 1636 roku = Capitula generalia basilianorum ab anno 1617 ad annum 1636 (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, сек. 1, т. 55), Рим, Львів: Місіонер, 2017, с. 450. The rules for serving the reader were established, that is, borrowing and returning books and the responsibility for this. Later, with the development of areas of religious and secular education for the monks of this order, the concept of the library was specified. In the Constitutions of the Basilians from 1773, collecting books is presented above all as an aid for those monks who study.3Constitutiones examinandae et seligendae in futuris capitulis sive Constitutiones in monasterio Hoscensi formatae, Vilnae: Typis Basilianis, 1773, p. 150. However, in practice the repertoire and scope of the library depended on various circumstances: the economic situation, the funding from benefactors, and the areas of activity of the monastic community.

The oldest written witness about the library of Holy Trinity Monastery dates to 1621. That year, at the chapter in Lavrishev, it was ordered that other monasteries return library books to the Vilnius monastery.4Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік, с. 143. This book-collection was one of the largest in the whole Basilian Order, inasmuch as the monastery was located in the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania; more so, theology was studied and a printing press functioned at the monastic center (↑), and there was also cooperation with Vilnius University. The library had losses more than once (especially in the times of war and epidemic in the middle of the 17th century, start of the 18th century, and in 1812), and, nevertheless, with the end of the difficult periods, as the monastery was renewed, so always was its book-collection.

The Vilnius Basilians actually possessed not one but several libraries, which had various designated goals. In the sacristy of a monastery church, there were holding a collection of books for worship which were used during Liturgy and other services. (In 1774, there were 50 copies, and 65 in 1823.)5СПбИИ РАН, ф. 52, оп. 1, д. 297, л. 12–13 об.; VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. (A750) 28491, l. 23. The monastery choir had a separate collection of musical works with sheet music. (In 1774, there were 188 manuscripts and printed copies.)6Ivanas Almesas, “Biblioteka”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 200; same: Іван Альмес, “Бібліотека”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 291–300. The Basilian rule required the reading of spiritual literature in the refectory, and this literature also formed a separate collection (the Bible, lives of the saints, decrees of church councils).7LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 81, l. 11r. And at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, a fund of textbooks was formed at the monastery, designated for those monks of the order who attended lectures at the university. (In 1823, 71 copies were counted.) (↑) 8VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. (A750) 28491, l. 138–139. In contrast with collections (for the worship, choir, refectory, and for students), which should be considered auxiliary, the main library was significantly larger and more complete.

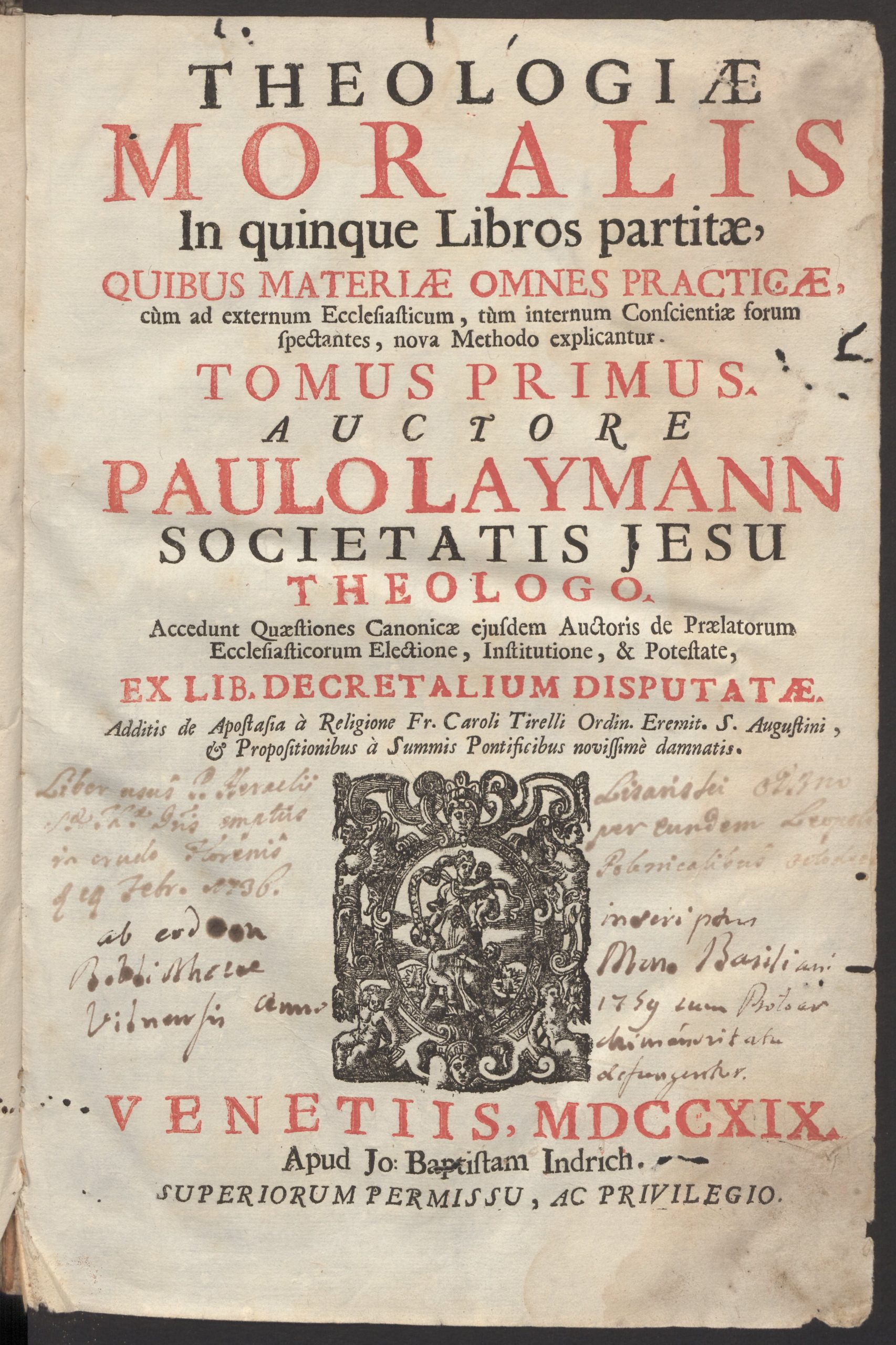

Premises with bookshelves were given for the main monastery book-collection. The books were arranged by a call number composed of three Roman and Arabic numbers, which indicated the shelf, section, and place on the shelf. On the spine of the binding the author or title was written. The library was enriched by various sources. First of all, funds from the monastery’s income were allotted to acquire books. In 1767, for example, 90 złoty were spent on this,9LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 1, l. 24v. and the next year, in May, for buying books in Rome 450 złoty and in June, 486 złoty.10Ibid., l. 28r, 28v. In addition, there were also payments for the bookbinding of library copies.11Ibid., l. 46v, 47v. Another source of acquisitions was the output of the local Basilian printing house (↑). Without a doubt, the funds increased thanks to the monks’ personal books. In this way, a work of moral theology by famous Austrian theologian Paul Laymann made its way to the monastery’s book-collection; the owner was Herakliusz Lisański, secretary of the Lithuanian Province of the OSBM [1]. When Basilian Innocent Knieżyński, a professor of Vilnius University, died in 1793, a copy from his collection, with an inscription about ownership, “P. Innocenij Knieżyński OSBM”, was given to the library’s section “Philosophy, Physics, Mathematics, and Medicine”. Marks of ownership on books make it clear that gifts from authors also enriched the library. In particular, in 1692 the Jesuit Teofil Rutka signed a book with theological content for the Basilian monastery “Caenobio f-rum Basilianorum apud SS. Trinit. Vilnae manentium A humillime offert d. d. c. 1692. 18”.12Teofil Rutka, S. Cyrillus patriarcha Alexandrinus summi pontificis Romani, caelestini in concilio Ephesino vicarius, idemque spiritus s. a filio procedentis de caelo datus propugnator, et negantium Spiritus Sancti ex filio processionem ante tempus, et tamen in tempore acerrimus expugnator. E suis monumentis ad vitam oculosq. posterorum de Graecia a P. Theophilo Rutka Societatis Jesu Theologo excitatus, Lublini: Typis collegii Societatis Iesu, 1692, 4° (LMAVB, XVII/560 [inscription on the title page]).

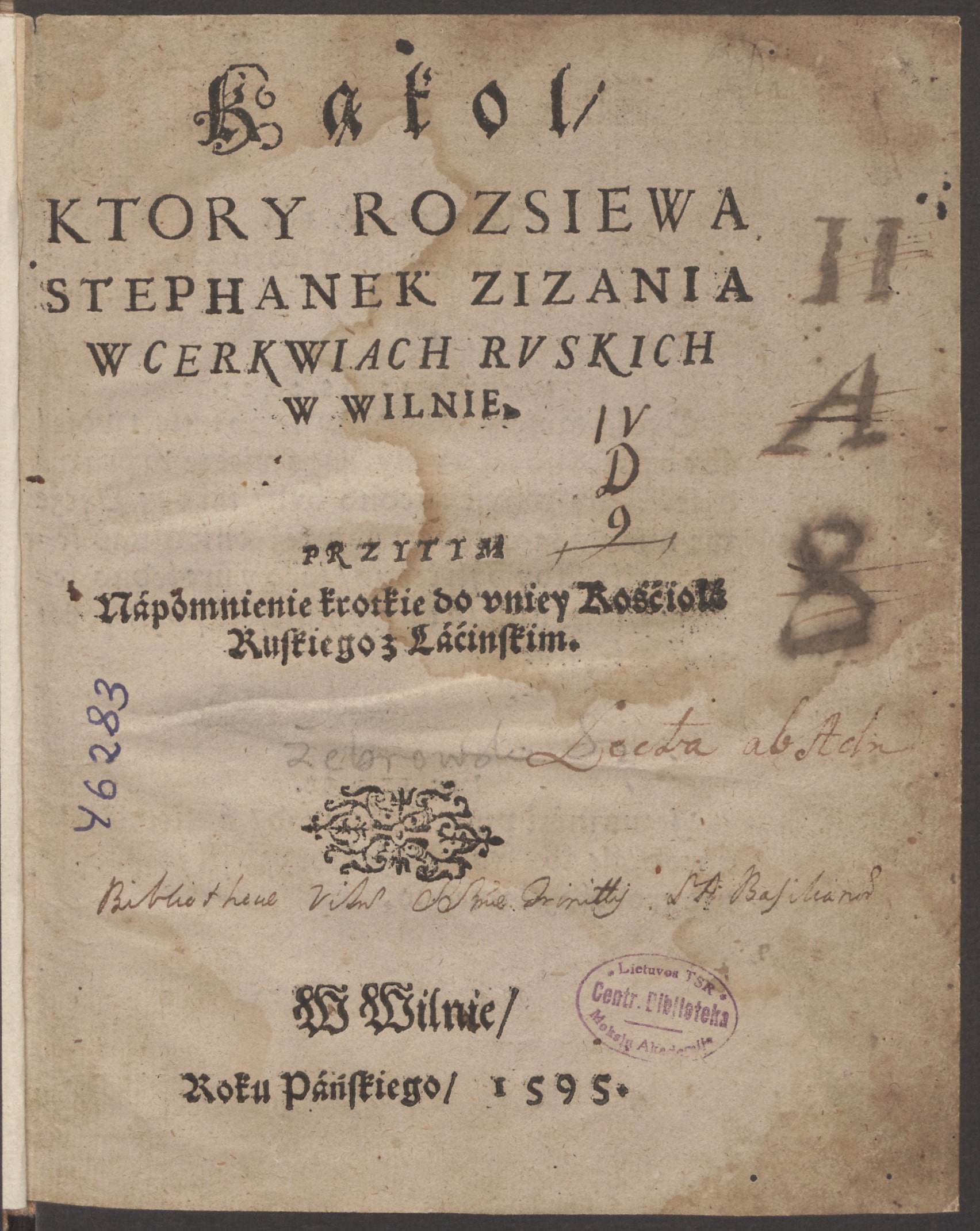

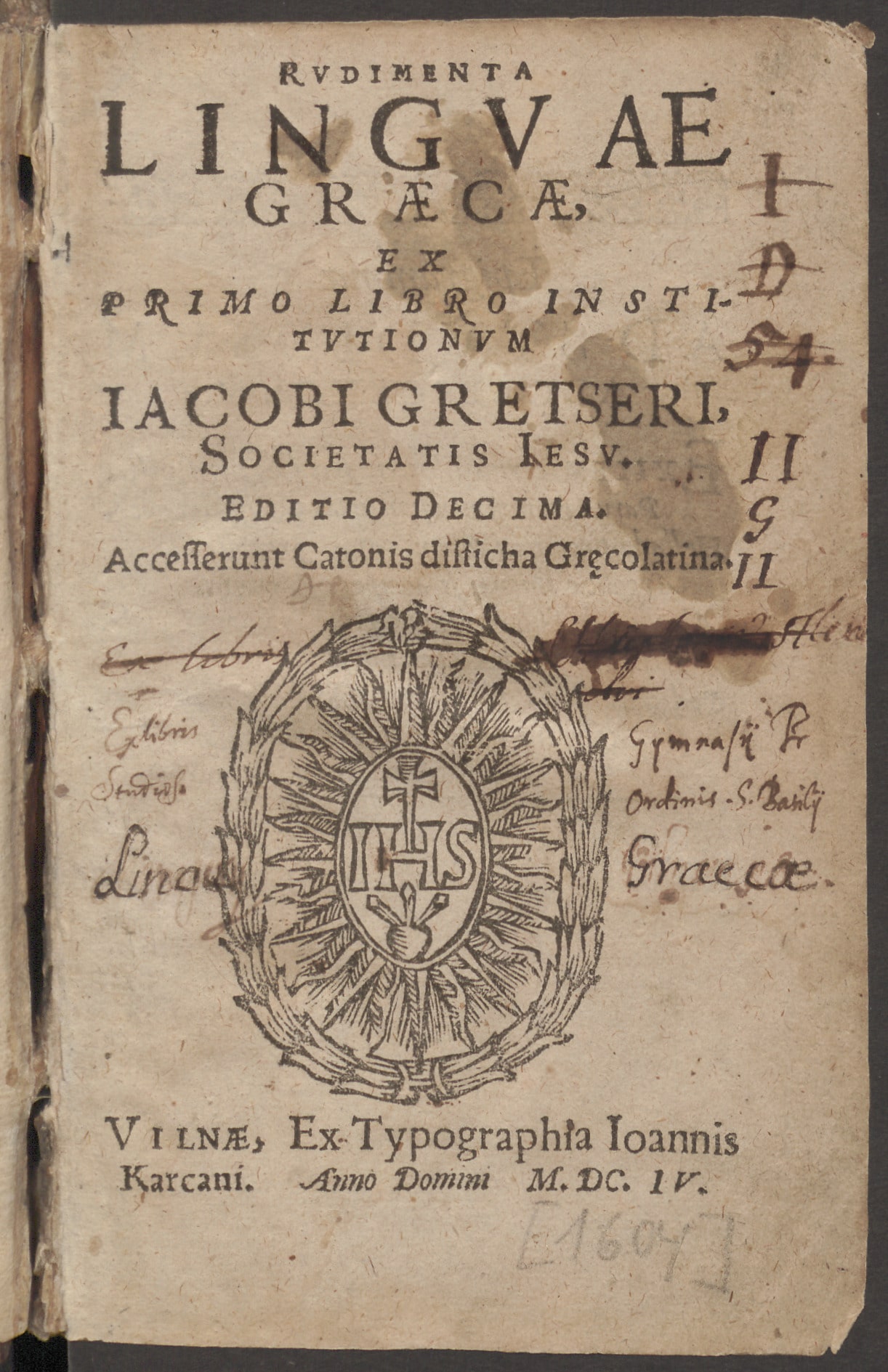

In the main library, literature was collected with attention to the monks’ intellectual needs. In the absence of library catalogues, it is possible to judge about the content of the collection of the 17th century from surviving copies and references to them in historic sources. It is considered that texts came to this book-collection on the basis of which the first publications of worship of the Uniates were prepared. Those Basilians who took part in interconfessional polemics needed appropriate books (↑) (↑). Their copies also remained in the library’s funds, like the polemical tractate of 1595 against Orthodox preacher Stefan Zizanij [2]. Of course, works of devotional literature were in largest demand; the monks borrowed them for their spiritual exercises. Works of theology and philosophy were collected for those studying theology, as were language learning material (handbooks, chrestomathies, dictionaries). Among the grammar books, a majority were for the study of the Greek language. Greek textbooks by Jakob Grettser, the oldest of which was a 1604 edition of Vilnius printer Jan Karcan, were used most often [3]. The local printing house (↑) also served to reprint the texts from books in the library. For example, in 1760 the printers used copy from the library to reprint the spiritual meditations of St. Augustine.

It is necessary to note that in the documents of the monastery from the 17th to the start of the 19th centuries the names of the monks responsible for the book-collection are not mentioned. Clearly, the obligations of the librarian were considered temporary.

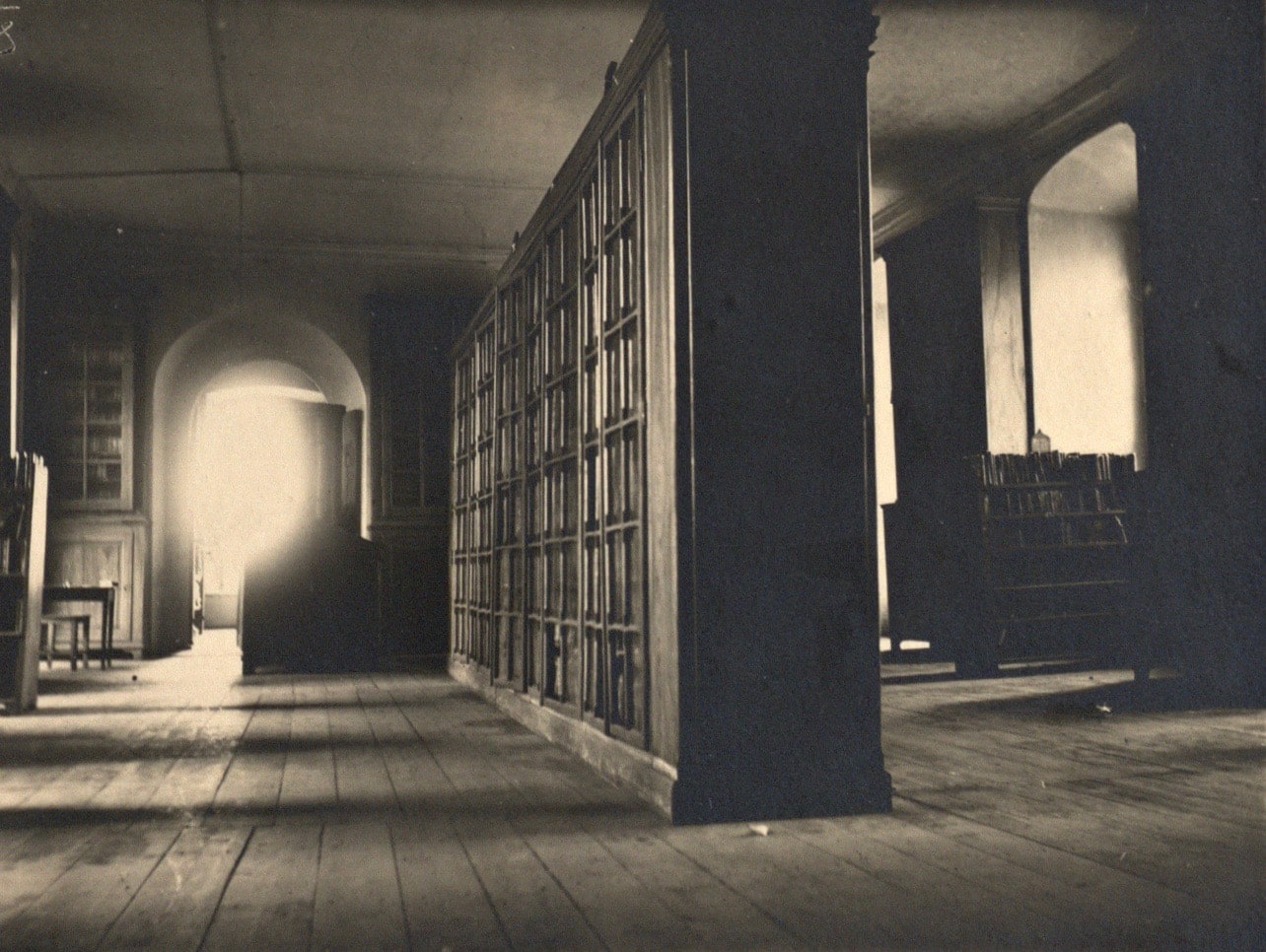

At the end of the 18th century, the library was flourishing: in the annex of the monastery corpus, a special hall with new bookcases was provided (↑), and there were more than 6 000 copies in the book-collection. Together with traditional religious books, the number of works of secular literature in various European languages grew: in history and critical literature, 155 items; in geography, 73 items; in political science, 223 items; in scholarly and language encyclopedias, 102 items, etc.13Arvydas Pacevičius, Vienuolynų bibliotekos Lietuvoje 1795–1864 metais: dingęs knygos pasaulis, Vilnius: Versus aureus, 2005, p. 159.

In 1839, when Vilnius Basilian monastery was joined to the Orthodox Church, the library remained in its old premises. From 1845, Orthodox seminarians used its funds. In the first half of the 20th century, the Vilnius Orthodox seminary was closed, and the Polish authorities decided to transfer the former book-collection of the Basilians to the Wroblewski Library [4].14VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 47, b. 945, l. 74r. (The Basilian library stocks were moved to a new place during the Second World War.) Today a significant part of the historical library of the Basilian monastery is preserved in the Wroblewski Library of the Academy of Sciences of Lithuania.

Ina Kažuro

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Pietro Menniti, Szkoła bazylianska zamykająca nauki dla dobrego wychowania nowiciuszow i professow Z.S. Bazylego W., Wilno: W drukarni J. K. M. XX. Bazylianow, 1764, s. 251. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пьєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік = Bazyliańskie kapituły generalne od 1617 do 1636 roku = Capitula generalia basilianorum ab anno 1617 ad annum 1636 (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, сек. 1, т. 55), Рим, Львів: Місіонер, 2017, с. 450. |

| 3. | ↑ | Constitutiones examinandae et seligendae in futuris capitulis sive Constitutiones in monasterio Hoscensi formatae, Vilnae: Typis Basilianis, 1773, p. 150. |

| 4. | ↑ | Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік, с. 143. |

| 5. | ↑ | СПбИИ РАН, ф. 52, оп. 1, д. 297, л. 12–13 об.; VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. (A750) 28491, l. 23. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ivanas Almesas, “Biblioteka”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 200; same: Іван Альмес, “Бібліотека”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 291–300. |

| 7. | ↑ | LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 81, l. 11r. |

| 8. | ↑ | VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. (A750) 28491, l. 138–139. |

| 9. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 1, l. 24v. |

| 10. | ↑ | Ibid., l. 28r, 28v. |

| 11. | ↑ | Ibid., l. 46v, 47v. |

| 12. | ↑ | Teofil Rutka, S. Cyrillus patriarcha Alexandrinus summi pontificis Romani, caelestini in concilio Ephesino vicarius, idemque spiritus s. a filio procedentis de caelo datus propugnator, et negantium Spiritus Sancti ex filio processionem ante tempus, et tamen in tempore acerrimus expugnator. E suis monumentis ad vitam oculosq. posterorum de Graecia a P. Theophilo Rutka Societatis Jesu Theologo excitatus, Lublini: Typis collegii Societatis Iesu, 1692, 4° (LMAVB, XVII/560 [inscription on the title page]). |

| 13. | ↑ | Arvydas Pacevičius, Vienuolynų bibliotekos Lietuvoje 1795–1864 metais: dingęs knygos pasaulis, Vilnius: Versus aureus, 2005, p. 159. |

| 14. | ↑ | VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 47, b. 945, l. 74r. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Paul Laymann, Theologia moralis, Venetiis: Apud Blasium Maldura, 1719, 2°. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, V-18/2-360. |

| 2. | Szczęsny Żebrowski, Kąkoł, który rozsiewa Stephanek Zizania w cerkwiach ruskich w Wilnie, W Wilnie, 1595, 4°. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, L-16/9. |

| 3. | Jacob Gretser, Rudimenta linguae Graecae, ex primo libro Institutionum, Editio decima, Vilnae: ex typographia Ioannis Karcani, 1604, 8°. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, L-17/168/1. |

| 4. | Held in: VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, F47-945. |