The tragic loss of Archbishop of Polotsk Josaphat Kuntsevych in Vitebsk on 12 November 1623 had a tremendous influence on the interconfessional situation in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Ukrainian lands of the Commonwealth [1].

Ivan (secular name) was born in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, though his spiritual formation and pastoral activities happened in Vilnius, where he moved when he was 16. The young man’s spiritual, cultural and general worldview began to form in the home of Vilnius merchant Yakynt Popovych. Later, during his beatification process, there was testimony that the young Kuntsevych privately studied philosophy and theology in the Polish and Ruthenian languages and also became deeply faithful.

Kuntsevych had close relations with the seminary at Holy Trinity Monastery; one of his mentors was Józef Welamin Rucki (↑). It is credible that in 1604 the 24-year-old Ivan entered Holy Trinity Uniate Monastery. (He received monastic tonsure before 1607.) Eventually, Hypatius Pociej ordained him as a deacon. It is considered that Kuntsevych himself revived community monastic life in the monastery. His contemporaries enthusiastically spoke of his talent as preacher and pastor.1Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 80–84; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2017, с. 92–97.

Kuntsevych went through a serious trial in December 1608, when the citizens of Vilnius and the clergy of local churches raised a riot against Metropolitan Hypatius Pociej (↑). After this, Kuntsevych finally decided to become a priest and, between the end of 1608 and the start of 1609, he was ordained a priest. With the nomination of Józef Welamin Rucki as archimandrite of Vilnius and metropolitan successor, responsibility for the monastic community and church order at the Vilnius monastery lay on Kuntsevych. In the second decade of the 17th century, for some time he was acting archimandrite of Holy Trinity (1612–1617) [2, 3].

In 1617, Kuntsevych was nominated to the Polotsk cathedral of the Kyivan Uniate Metropolitanate [4], where he launched tumultuous activity, aimed above all at disciplining the clergy and faithful, for the area held exceptionally strongly to Orthodox traditions. He renewed the Cathedral Church of St. Sophia in Polotsk and strengthened the cathedral administration. He attended a session of the Sejm in Warsaw and appealed to the king’s authority and the leadership of the Catholic Church. Desiring to convince the faithful, he focused his attention on Orthodox opposition to the Union in Vitebsk, Polotsk, and Mogilev, where, from time to time, opposition to his administrative activities arose. Finally, methods which bordered on violence against the faithful caused the Vitebsk tragedy of 1623 [5].

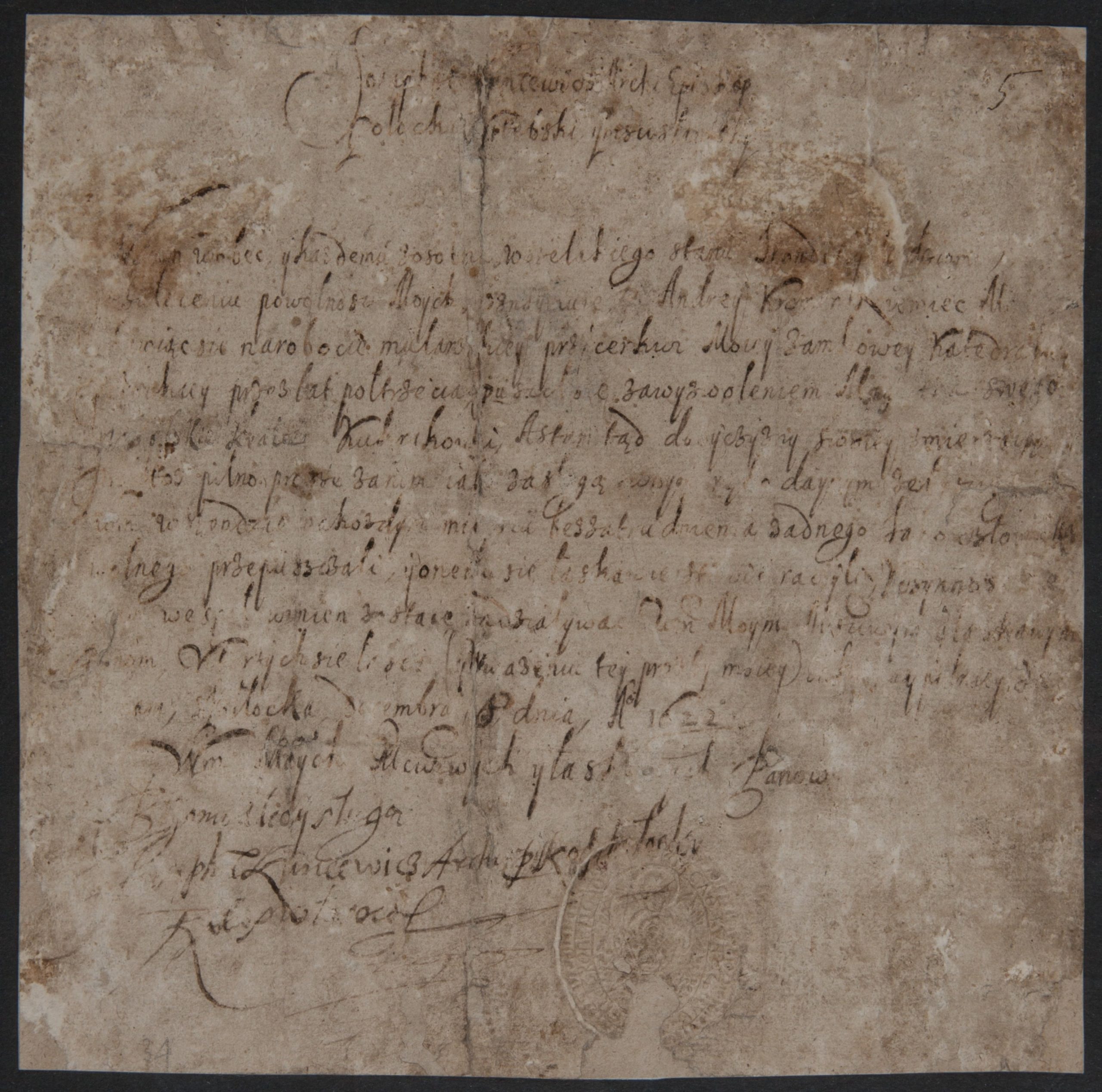

The preserved correspondence and polemical literature of this time illustrate an exceptionally complicated situation in the Polotsk Archeparchy, to which in 1620 the Orthodox nominated Melecjusz Smotrycki. As a consequence of this act, interconfessional relations worsened, for both bishops wanted to subject the parishes and faithful to their authority. In fact, Smotrycki’s authority over the archeparchy was weak and, fearing persecution, he did not leave the confines of Holy Spirit Monastery. However, Kuntsevych’s power was not firm, which numerous conflicts with the archbishop in various areas confirmed. The standing of the Uniate archbishop was legitimate from the point of view of recognition by the king’s administration. The day before the Vitebsk tragedy, secular magnates and government officials warned Archbishop Kuntsevych of the risk of using pressure on the Orthodox. The sources witness that Kuntsevych knew that they could kill him and he consciously went to his death.

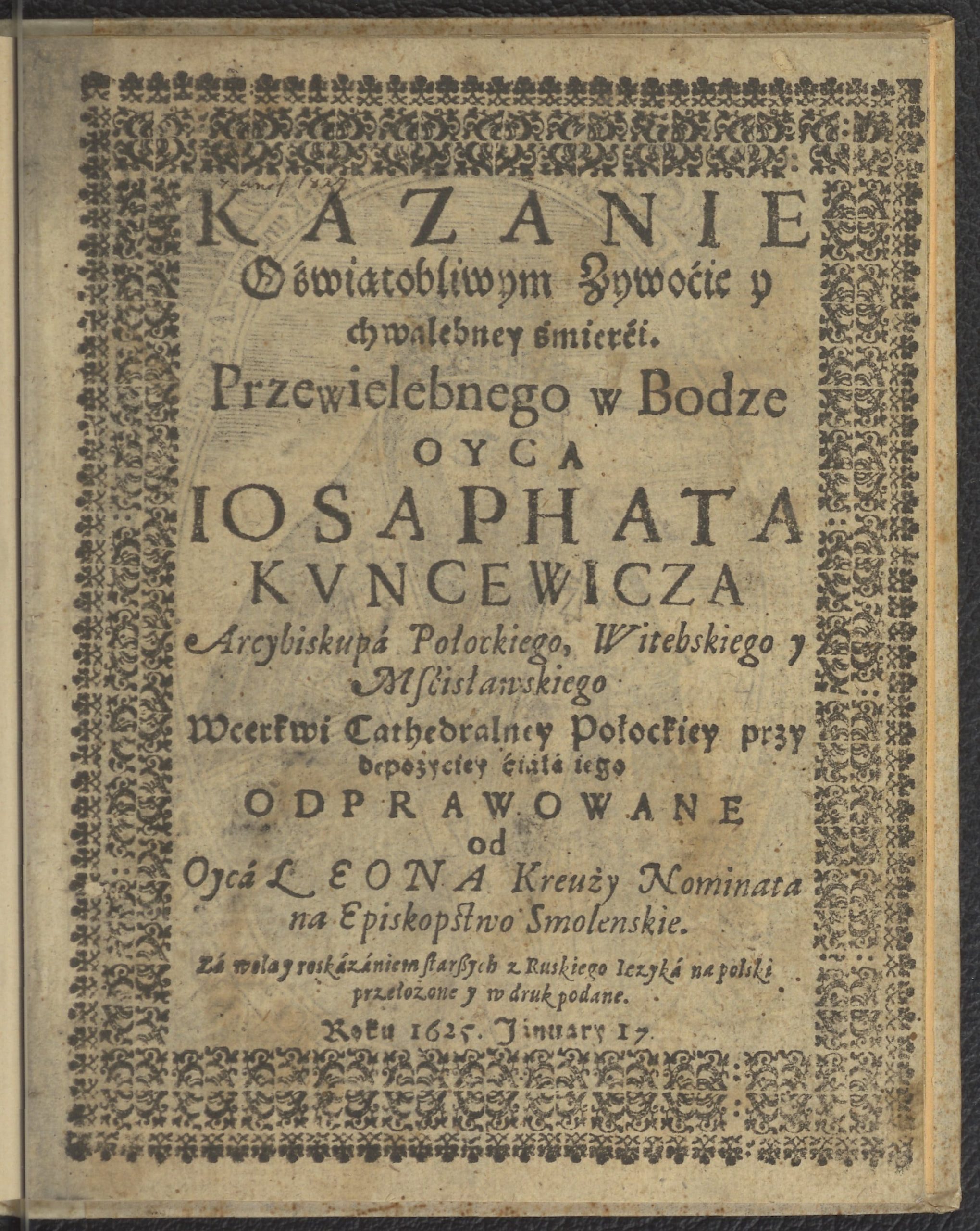

In addition to witnesses in the beatification process,2S. Josaphat Hieromartyr: Documenta Romana beatificationis et canonizationis, т. 1: 1623–1628 (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 3: Documenta Bio-Hagiographica ex Archivis Romanis, т. 1), ред. Athanasius G. Welykyj, Romae: PP. Basiliani, 1952. immediately after Kuntsevych’s death two narratives about the martyr, with a hagiographical character, were published: a text of Metropolitan Józef Welamin Rucki about Kuntsevych’s life and death (sent to Rome at the start of April 1624)3Йосафат Скрутень, “Перший життєпис св. Йосафата”, in: Analecta OSBM, сер. 1, т. 1, ч. 2–3, Жовква, 1924, с. 314–363. and a work of Ioachimus Morochowski, published in 1624 in Zamość.4Relacia o zamordowaniu okrutnym, y osobliwej Swiatobliwośći w Bodze Wielebnego Oyca Iozaphata Kuncewicza Archiepiszkopa Połockiego krotko a prawdziwie opisana. W Zamosciu, Roku Panskiеgo 1624. Though published in 1625, the funeral sermon of Leon Kreuza at the burial of Kuntsevych in Polotsk was epochal (date of publication, 17 January). As is known, after his tragic death, Kuntsevych’s body was taken to Polotsk and placed in a coffin at the altar of a locked church. The ceremonial funeral procession was held on 27–28 January. Kreuza’s sermon was proclaimed on 28 January.5See: Мелетій М. Соловій, Атанасій Г. Великий, Святий Йосафат Кунцевич. Його життя і доба, Торонто: Вид-во оо. Василіян, 1967, с. 323–327.

As of today, there are four known copies of Kreuza’s sermon preserved: the Lviv, Vilnius, Warsaw, and Moscow copies. The full name of the memorial: “KAZANIE O swiatobliwym Zywoćie y chwalebney śmierći. Przewielebnego w Bodze Oyca IOSAFATA KYNCEWICZA Arcybiskupa Połockiego, Witebskiego y Msćisławskiego W cerkwi Cathedralney Połockiey przy depozyciey ćiała iego ODPRAWOWANE od Oyca LEONA Kreuży Nominata na Episkopstwo Smolenskіе. Za wola y rozkazaniem starszych z Ruskiego ięzyka na polski przełożone y w druk podane. Roku 1625. Ianuary 17” [6].

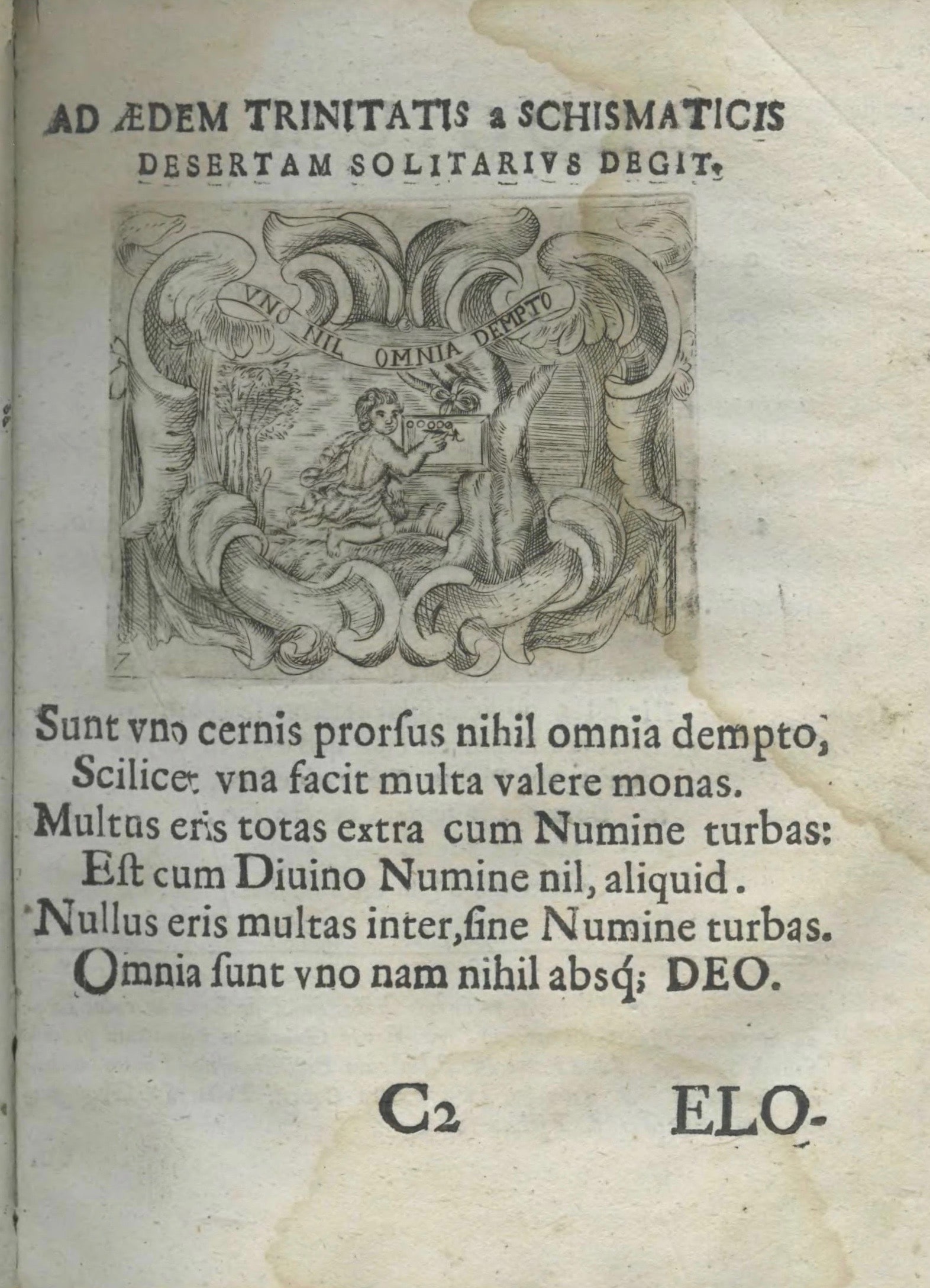

Already in the introduction, which is called “A sermon. The just man perishes in his justice”, and further in the text, the motto of the oration on Kuntsevych’s life and death is given, taken from the Old Testament Book of Ecclesiastes (Ecc. 7:15). Among the compendium of names of rubrics, the triad “faith, hope, charity” attractively stands out, the concept prudence, the rubric self-restraint, and examples of Josaphat’s asceticism (in the monastery, “he often wore three iron chains, joined by rings and hooks, two crossing over his shoulders and the third girded his thighs”). Clearly this refers to penitential chains which monks used. In Vilnius, as a monk Josaphat was often seen in severe frost at the cemetery behind Holy Trinity Church, where he prayed, standing on a stone in one garment and barefoot. (Here Kreuza is close to a characteristic phenomenon which in Eastern monasticism is known as “stylitism”), which in the mentioned example is a sign of asceticism and the monk’s clearly expressed holiness. With the example of Kuntsevych, Kreuza managed to create an ascetic monastic ideal, which was further developed in later biographies of the martyr.6Н. В. Синицына, “Типы монастырей и русский аскетический идеал (XV–XVI века)”, in: Монашество и монастыри в России: ХI–XX века, отв. ред. Н. В. Синицына, Москва: Наука, 2002, с. 118–149. The author of the sermon lists the obligations which he often carried out in the monastery: candle-bearer, singer in the choir, helper in the sacristy, confessor, teacher of the faithful, etc. And so here he spent all his time when free from official services, in prayer. The author also accents how widely-read Josaphat was, fluent in at least two languages, and he states, using the method of parable: “I dare say that in the whole Duchy of Lithuania there was no Slavic and perhaps also Polish book which he had not read.” Similar to the previous is the small rubric monastic life, which includes the rubric faith, a short rubric hope, and interesting rubrics charity and signs of charity.

The extreme character of Josaphat’s death allowed Kreuza to create an image of a martyr like Christ, that is, a martyr for the faith. In fact, the topos of martyrdom is at the core of the whole work. For evidence, the author of the panegyric compares the tragic death of Kuntsevych with the Savior’s death, using some pericopes from Holy Scripture (Mt 5:10, 23:35; Ja 2:22; Jn 3:12; Ti 1:16; 2 Mac 7:1), which are examples of a martyr’s death for the faith by way of not renouncing God (textbook examples of the death of Abel at the hand of his brother Cain, the blood of Zacharias, son of Barachias, and the murder of the Maccabee brothers by Antiochus). Kreuza explores the topos of innocence surprisingly with outstanding argumentation. The final part of the second section is very emotional and has the character of pastoral instruction and warning. Also, exalted and emotional, Kreuza promises revenge on those guilty of the tragedy.

The canvas of chronology and facts in the sermon is rich and outstanding. With a view to the use of Old Testament and New Testament pericopes, the sermon of Kreuza fits in and yet does not among the famous examples of Ukrainian-Belarusian funeral literature. This is a typical example of preaching at the time, which intertwines eastern and western religious-theological learning, with clear dominance of the latter.7See more: Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 453–524.

A woodcut portrait which gives a realistic illustration of Josaphat, very different from later iconography, is extremely important [1].8See more: Jolita Liškevičienė, “Ankstyvieji palaimintojo Juozapato Kuncevičiaus portretiniai atvaizdai”, in: Dangiškieji globėjai, žemiškieji mecenatai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 60), sud. Jolita Liškevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 113–125. In the 17th century, biographical literature gradually arose which, with a view to the basics of the genre, to a significant extent mythologized the saint’s biography.

In 1655, when the Muscovite army took Polotsk, Metropolitan Antoni Sielawa brought Kuntsevych’s body to Zhyrovichy monastery and then to Zamość. Later the body was returned, though, after Moscow took Polotsk at the start of the 18th century, the relics were brought to a castle chapel in the city of Biała Podlaska, where they remained until 1764. Only in 1917 were the relics brought to Vienna, and since 1946 they have been preserved at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Kuntsevych was beatified in 1642 by Pope Urban VIII [7] and canonized in 1867 by Pope Pius IX [8, 9].

Leonid Tymoshenko

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 80–84; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2017, с. 92–97. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | S. Josaphat Hieromartyr: Documenta Romana beatificationis et canonizationis, т. 1: 1623–1628 (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 3: Documenta Bio-Hagiographica ex Archivis Romanis, т. 1), ред. Athanasius G. Welykyj, Romae: PP. Basiliani, 1952. |

| 3. | ↑ | Йосафат Скрутень, “Перший життєпис св. Йосафата”, in: Analecta OSBM, сер. 1, т. 1, ч. 2–3, Жовква, 1924, с. 314–363. |

| 4. | ↑ | Relacia o zamordowaniu okrutnym, y osobliwej Swiatobliwośći w Bodze Wielebnego Oyca Iozaphata Kuncewicza Archiepiszkopa Połockiego krotko a prawdziwie opisana. W Zamosciu, Roku Panskiеgo 1624. |

| 5. | ↑ | See: Мелетій М. Соловій, Атанасій Г. Великий, Святий Йосафат Кунцевич. Його життя і доба, Торонто: Вид-во оо. Василіян, 1967, с. 323–327. |

| 6. | ↑ | Н. В. Синицына, “Типы монастырей и русский аскетический идеал (XV–XVI века)”, in: Монашество и монастыри в России: ХI–XX века, отв. ред. Н. В. Синицына, Москва: Наука, 2002, с. 118–149. |

| 7. | ↑ | See more: Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 453–524. |

| 8. | ↑ | See more: Jolita Liškevičienė, “Ankstyvieji palaimintojo Juozapato Kuncevičiaus portretiniai atvaizdai”, in: Dangiškieji globėjai, žemiškieji mecenatai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 60), sud. Jolita Liškevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 113–125. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | [Wawrzyniec Leon Kreuza-Rzewuski], Kazanie o świątobliwym zywocie y chwalebney śmierci przewielebnego w Bodze oyca Iosaphata Kuncewicza, arcybiskupa połockiego, witebskiego y mscisławskiego w cerkwi cathedralney połockiey przy depozyciey ciała iego odprawowane… [S. l., 1625]. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, XVII/101/10; BN, BN SD XVII.3.5729 (Available at: Polona, https://polona.pl/item/kazanie-o-swiatobliwym-zywocie-y-chwalebney-smierci-iosaphata-kvncewicza,ODU4MTExNjA/6/#info:metadata, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 2. | [Andrzej Mlodzianowski], Icones symbolicae vitae et mortis B. Josaphat martyris Archipiscopi Polocensis, expressae et Perillustri Domino…, Vilnae: Acad. Soc. Jesu, 1675, f. C2r. Held in: BK PAN, sygn. 11171 I (Available at: Wielkopolska biblioteka cyfrowa, www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/publication/460025/edition/369278?language=pl, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 3. | Ibid., f. C4r. |

| 4. | Held in: VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, F48-32663 (Available at: Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka. Skaitmeninės kolekcijos, https://kolekcijos.biblioteka.vu.lt/islandora/object/atmintis%3AVUB01_000393658#00001, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 5. | Held in: MNW, MP 686 MNW (Available at: Cyfrowe zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/510968, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 6. | [Wawrzyniec Leon Kreuza-Rzewuski], op. cit. |

| 7. | Held in: BMP, BMP BP 104 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/76489160?s_id=eQ0NatWUtmky3qpY&s_ind=10&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). Published in: Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus. Muziejaus gidas, [Vilnius: Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus], 2010, p. 68–69; „Vilniaus katedros lobynas“, in: Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus, available at: http://bpmuziejus.lt/vilniaus-katedros-lobynas-2.html, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 8. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 9. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |