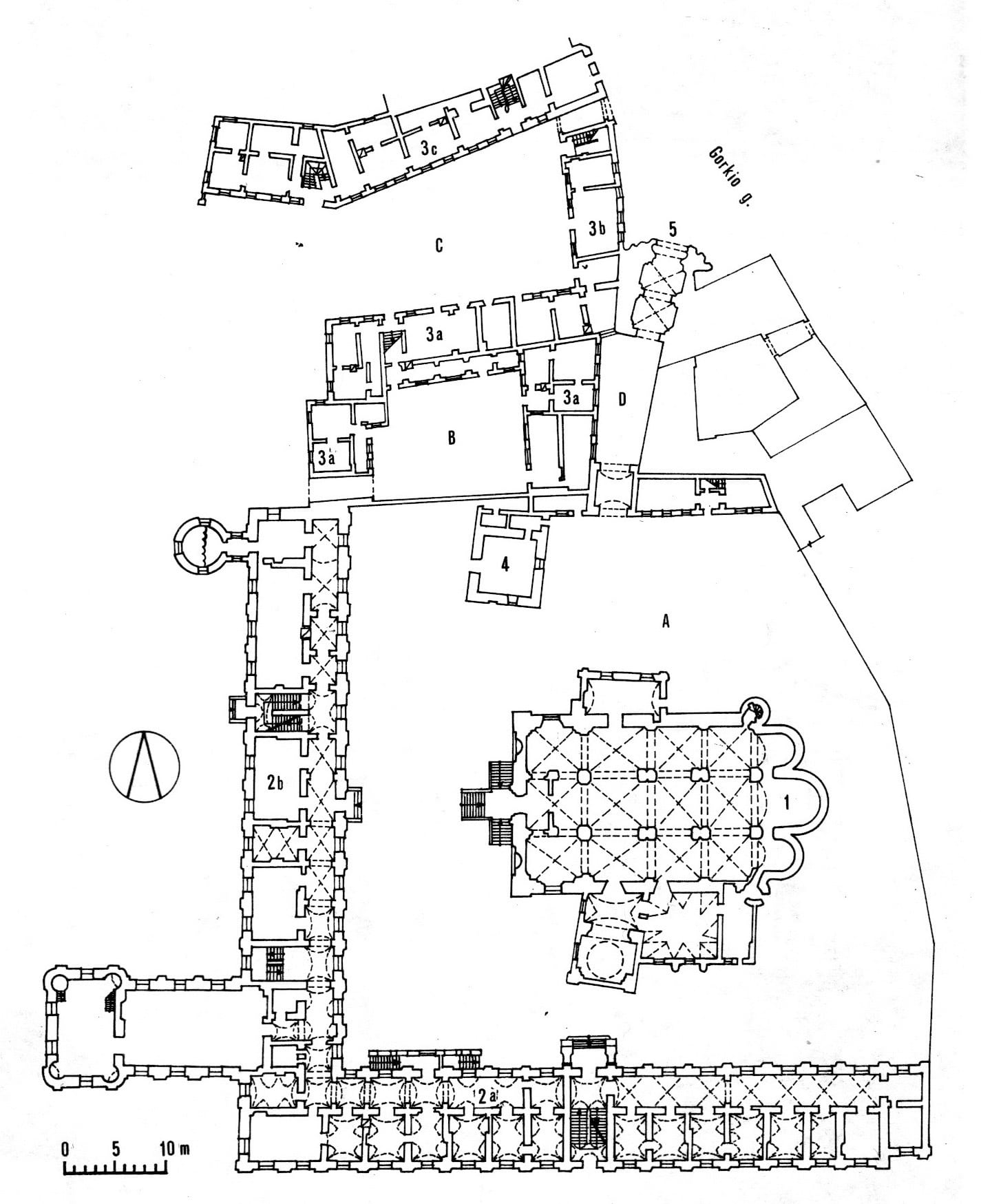

Holy Trinity Church in Vilnius with its men’s and women’s monasteries once took up a significant part of the Old City, which reached from today’s Aušros Vartų and Arklių streets [1, 2].1For a description of the boundaries of the jurisdiction at the beginning of the 17th century, see: Археографический сборник документов, относящихся к истории Северо-Западной Руси, издаваемый при управлении Виленскаго учебнаго округа, т. 10, Вильна: Печатня О. Блюмовича, 1874, с. 19–22. The territory of the ensemble was surrounded by a brick fence with a gate. The most impressive structure has been preserved – the main entrance, composed of two gates. The first, the Basilian Gate, constructed in 1761, is like the “calling card” of the whole ensemble and well seen from Aušros Vartų street [3]. The gate greets us with a very decorated façade with relief images of the Holy Trinity, which recalls the name of the church and monastery, and its dynamic, almost pulsing, baroque forms direct our gaze to the depth of the ensemble. Then past it we encounter the somewhat humbler second gate [4]. It was decorated with a painting of which only parts are preserved. Once there was an image of Josaphat Kuntsevych on the walls of this gate, still visible in 1837.2LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 220, l. 1. Some other elements of this entrance and the fence of the ensemble have partially survived [5].

The history of the brick Holy Trinity Church [6] begins at the start of the 16th century. The walls of the shrine, financed by the commander of the Lithuanian Army, Konstanty Ostrogski, still stand (↑). Though plaster and extensions of later times cover them, nevertheless, the splendor of this structure is still impressive. Research data demonstrates that features of the sacred architecture of Eastern and Western Christians were intertwined in it. Almost square in plan, with three semicircular apses in the eastern part, it has the typical sign of Orthodox architecture. On the other hand, four pillars (support columns) inside the building, which support not the cupola but the vaulting, is characteristic of Roman Catholic churches.3Algė Jankevičienė, “Dviejų stilių sintezė XVI a. Vilniaus cerkvių architektūroje”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės gotika: sakralinė architektūra ir dailė (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 26), Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2002, p. 173. These pillars have lasted to our days, though, at the end of the 18th century, capitals of the forms of early classicism still adorned them. Four new pillars, constructed in the 18th century in the process of reconstruction of the shrine, have such capitals [7]. A high, two-sloped roof, three-cornered gables with facades, and stepped buttresses, which fortify the walls, are gothic elements also adopted from church architecture of the 16th century. Unfortunately, as a consequence of later rebuilding, they were lost and are now being restored according to the reconstructions of scholars. A few remains of this period are centered in the eastern part of the church (in the back façade): a relief ornamental strip of small arches on the walls of the apses and two corner towers of a round profile with a spiral staircase that leads to the loft (the upper rungs of the towers were built after 1760, which their baroque style shows). Authentic masonry of the 16th century is also exhibited here, opened in 2018 during restoration. This masonry is a characteristic cruciform ornament, created by using bricks of red and yellowish colour [8]. The whole church was bricked in this way.

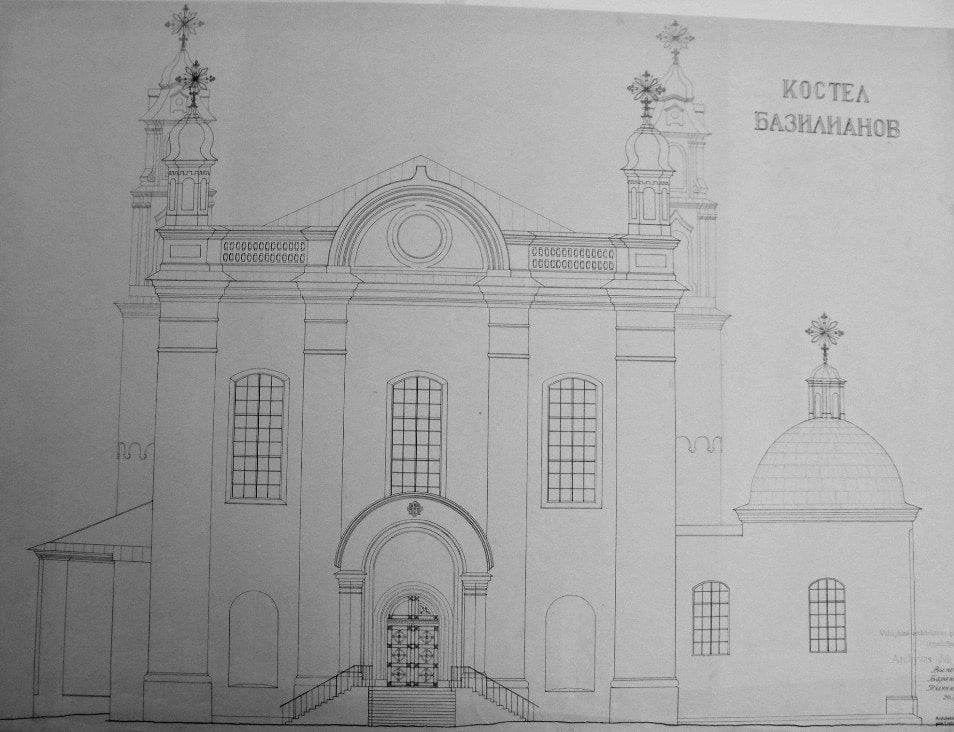

The main (western) façade of the church has not been preserved. It was demolished in 1792 with the extension of this sacred building to the west. The place of the old façade is now marked with a vertical “exposure”, done by restorers in the northern wall [9]. What remains of the main façade constructed in the 18th century are vertical pilasters and semicircular niches (only the painting in them is from the end of the 19th century). Its upper part was rebuilt in 1869. Through this last reconstruction of the church, they wanted to give features of Byzantine architecture: the classical triangular gable was destroyed, side towers were built, and a balustrade, which joined them [10, 11].

In 1792, the windows of the building were enlarged, and its interior was changed: the vaulting was reworked or entirely rebuilt, and also new organ choirs were established [12]. This can all still be seen today (↑) (↑).

In the 17th century, several chapels were added to the church. Their outside forms have been preserved. The Chapel of St. Luke is adjacent to the north side façade of the church [13]. In 1792, it was joined with the bell tower and women’s monastery by a brick corridor in the supports of the arches. In 1840, the corridor was demolished. Traces of it remain only in the bell tower and the chapel wall (the area of the former passageway to the chapel has been “exposed”; it is exhibited). The Chapel of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Mother of God or Chapel of the Skumins is located in the south side of the church [14]. It was rebuilt more than once, and in 1851–1852 and 1891 it was reconstructed and expanded, joining it with the former sacristy and a part of the corridor which led from the church to the men’s monastery.4Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 220, 223; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 324, 328. At that same time, two doorways were cut from the chapel to the church, which we still see now. The main architectural jewel of this worship building is a cupola which gives the whole space ceremony and harmony. Architectural traces of the Chapel of the Exaltation of the True Cross, which was located on the south side of the church, are best seen from outside. In the 18th century, it was turned into a sacristy and in the 19th century combined with the Chapel of the Skumins. At the end of the 18th century, behind the chapels of the Skumins and the Exaltation of the True Cross (from the south side of the church, closer to the back façade) a corridor was built which connected the church and the men’s monastery. In 1869 it disappeared, and only in the 21st century was it partially rebuilt. In 2009, the exhibit “Konrad’s Cell” was set up here. It recalls the jail into which the monastery was transformed in the first half of the 19th century, and also Adam Mickiewicz, who was imprisoned there, and his noted poem “Dziady”. (In fact, the poet was imprisoned in other premises, so the modern exhibit has an essentially symbolic meaning.)

The church is surrounded by a churchyard. In earlier times, there was a cemetery here, and in the 19th century flower beds are mentioned. Other structures of the ensemble were located around the churchyard.

The bell tower soars on the right, at the entrance to this territory through the main gate [15]. It arose in the second half of the 16th century. Once it was significantly higher, bells hung in it, and it had a clock. The building has features of Renaissance style. Now only its lower part remains.5Algė Jankevičienė, “Dviejų stilių sintezė…”, p. 174. Also, earlier the walls of the bell tower were divided by high windows, which ended in semicircular arches. They were bricked over in the 18th–19th centuries, but their traces are still well visible from inside. Next to the bell tower a fence remains, which separated the men’s and women’s monastic centers. Left of the gate is the building of the former bursa (monastery school). It was built at the end of the 18th century, on the site of old buildings, perhaps of the 15th–16th centuries. It was possible to go from the bursa to the extension over the main entrance of the second gate and to the balcony designated for musicians on the façade of the main, Basilian Gate.

The men’s monastery occupied the space west and south of the churchyard. In the second half of the 18th century, the main residential buildings of the monastery, which still stand, were built on this territory. The architecture is unpretentious but solidly built. Their calm facades are divided by rows of windows and pilasters. The three-story western building, with a “back” side (opposite the churchyard), has two extensions: an annex, which branches out from it, and a rounded extension (from the second half of the 19th century in the form of a tower) [16].6A. Jankevičienė, V. Levandauskas, “Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno pastatų ansamblis M. Gorkio g. 71, 73”, in: Vilniaus architektūra, sud. A. Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1985, p. 168. The southern corpus has three floors with a semibasement. The northern wall of this structure (facing the yard) stands on a foundation laid in the 17th century, and its southwestern part was established much earlier, between the end of the 16th and the start of the 17th centuries [17].7Tauras Poška, “Bazilijonų vienuolynas Vilniuje, Arklių g. 18–Aušros Vartų g. 7”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2005 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2006, p. 218–219. Authentic details are preserved within the buildings: vaulting, niches, and parts of wall paintings from the end of the 18th and second half of the 19th centuries. However, a number of things were ruined during remodeling that happened in the 19th–20th centuries, and then the planning of the premises was changed. In 2004, the western corpus was adapted for the needs of an educational institution: ISM University of Management and Economics was located here. (The head of the adaptation project was Alina Samukienie). Throughout 2005–2006, the southern corpus was adapted for the Basilian monastery (project head, Virginia Bakšiene) (↑).

The buildings of the former women’s monastery form the northern part of the ensemble [18]. This complex was formed in the 17th–18th centuries, uniting a few small brick buildings of the 15th–16th centuries around two courtyards. The brickwork of the walls of that time are open on today’s facades. The doorways and entrance gates have been restored. The outside forms of individual structures which existed before they were united have been visually separated. Apartments have been established in these buildings and various organizations operate here [19] (↑).

Rūta Janonienė

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | For a description of the boundaries of the jurisdiction at the beginning of the 17th century, see: Археографический сборник документов, относящихся к истории Северо-Западной Руси, издаваемый при управлении Виленскаго учебнаго округа, т. 10, Вильна: Печатня О. Блюмовича, 1874, с. 19–22. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 220, l. 1. |

| 3. | ↑ | Algė Jankevičienė, “Dviejų stilių sintezė XVI a. Vilniaus cerkvių architektūroje”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės gotika: sakralinė architektūra ir dailė (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 26), Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2002, p. 173. |

| 4. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 220, 223; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 324, 328. |

| 5. | ↑ | Algė Jankevičienė, “Dviejų stilių sintezė…”, p. 174. |

| 6. | ↑ | A. Jankevičienė, V. Levandauskas, “Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno pastatų ansamblis M. Gorkio g. 71, 73”, in: Vilniaus architektūra, sud. A. Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1985, p. 168. |

| 7. | ↑ | Tauras Poška, “Bazilijonų vienuolynas Vilniuje, Arklių g. 18–Aušros Vartų g. 7”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2005 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2006, p. 218–219. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 2. | Published in: Vytautas Levandauskas, „Šventosios Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno ansamblis“, in: Lietuvos TSR istorijos ir kultūros paminklų sąvadas, t. 1: Vilnius, Vilnius: Vyriausioji enciklopedijų leidykla, 1988, p. 236 (il. 156). |

| 3. | Held in: KPC PB, f. 6, ap. 1, b. 3311. Published in: „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis“ [unique code: 681], in: Kultūros vertybių registras, available at: https://kvr.kpd.lt/#/static-heritage-detail/06cabf58-1daa-4641-af11-c7de1aa4f2c5, photo no. 25, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 4. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 5. | Private collection of Rūta Janonienė. |

| 6. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 7. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 8. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 9. | Ibid. |

| 10. | Ibid. |

| 11. | Held in: KPC PB, f. 6, ap. 1, b. 137. Published in: „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis…“, photo no. 26, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 12. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 13. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 14. | Ibid. |

| 15. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 16. | Collection of VU IF. |

| 17. | Ibid. |

| 18. | Ibid. |

| 19. | Private collection of Rūta Janonienė. |