In difficult times of ecclesial transformation, certain cities with their specific environments played a significant role in religious life. After the decline of Kyiv as a state and cultural center and the migration of the Kyivan Metropolitanate north, for a long time an atmosphere of orphanhood reigned, inasmuch as the metropolitans, residing in Vladimir on the Klyazma or Moscow, did not have the opportunity to appropriately develop the Kyivan Church beyond the boundaries of the Moscow area of the time.1See: Борис Ґудзяк, Криза і реформа: Київська митрополія, Царгородський патріapхат і ґенеза Берестейської унії, Львів: Інститут історії Церкви ЛБА, 2000, с. 4. Changes of ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the 15th–16th centuries, as a consequence of the battle for the legacy of Kyiv and one or another state factors or groups of influence and alternating interim rule from Moscow or Novogrudok, Vilnius or Halych, were unable to positively influence religious life, creating a number of crisis situations in the ecclesiastical organism.2Назар Заторський, «Послання Мисаїла до папи Сикста IV» 1476 року: реконструкція архетипу (series: Київське християнство, т. 15), Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2019, с. 19.

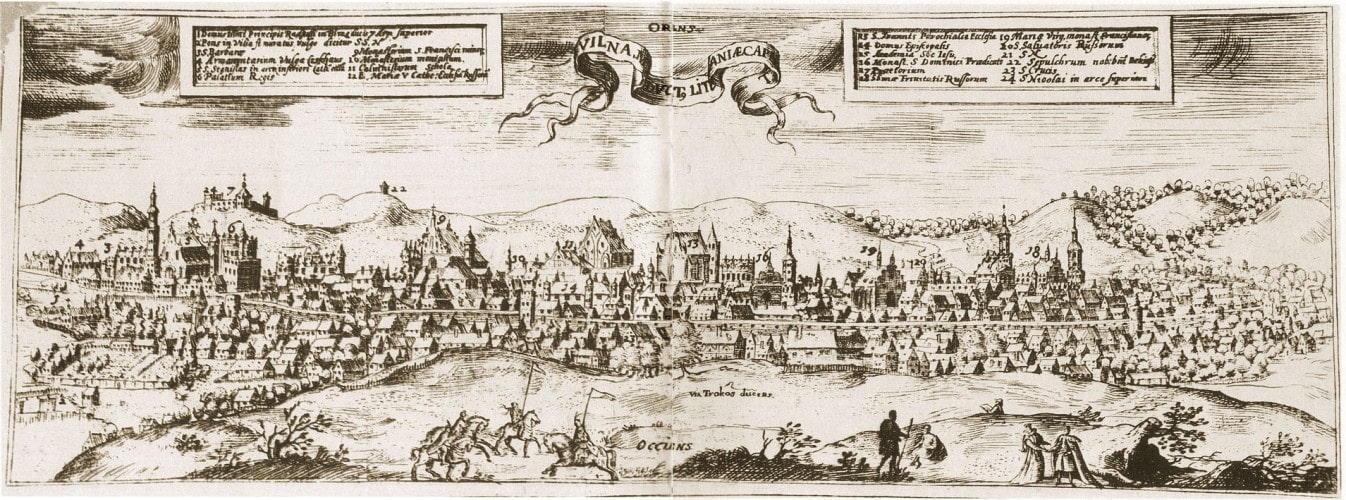

A number of ethnocultural and religious communities were concentrated in Vilnius in the 16th–17th centuries, thanks to which it was always a place with a unique “gravitation” for religiously active persons and groups [1]. Despite local particularities, the religious life of Vilnius, with insignificant difference, developed just as in other regions. The Church acted as a consolidating environment for civitas Ruthenica of Vilnius (↑) at that time, having such important elements of religious identity as: a Slavic-Byzantine liturgical rite; the Julian calendar; their own theological understanding (apologetic-polemic); a common sacra lingua – the Church Slavonic liturgical and Ruthenian “simple” languages; and their own particular ecclesiastical law and also a single canonical territory (↑).3See: Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Ukrainietiškoji perspektyva: Kijevo krikščionybės lietuviškųjų ištakų „prisiminimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 243–245; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Українська перспектива”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 365–366.

Already from the beginnings of the Christianization of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the religious factor became an outstanding marker of belonging in the opposition “ours – foreign” and an important element of possible discrimination on a confessional basis. Crisis situations were a significant stimulus for society to begin reflection on its religion, to seek out and formulate signs of its own “true faith” in opposition to the teaching of “apostates” and “heretics” of various kinds. An outstanding example of this assertion is the post-Tridentine reform of the Catholic Church.

Of course, interconfessional disputes were characteristic of urbanized environments, which were characterized by greater organization, for the rhythm of life was not so connected with the agricultural cycle. In this context, the role of church brotherhoods was important. They positioned themselves as defenders of “sacred antiquity”. We know about their active opposition to the future union, though, after the institutional confirmation of the Uniate Church. their role noticeably decreased (↑).

The Basilian monks significantly influenced the process of forming Uniate identity, especially after their reform, which Metropolitan Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky began already in 1617, uniting separate monasteries into one congregation on the example of Latin monastic orders [2].

Though the role of the Basilians sometimes led to the introduction of latinizing practices and even some destruction of the rite, nevertheless, considering all the aspects of religiosity in these times, it does seem that the Basilians were, perhaps, the most dynamic and relatively independent environment. Though the religious life of the Basilians was transformed under the influence of the Latins, it never faded, maintaining significant longevity. In a later period, more favorable conditions for the development of monasticism itself and the activization of wider pastoral activity began to appear. It is known that in Vilnius through the 17th century three general chapters of the Basilians were held, in 1636, 1650, and 1667, the acts of which focused on a wide spectrum of religious problems.4See: Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пьєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 2, т. 55), Рим, Львів: Видавницво Отців Василіян “Місіонер”, 2017.

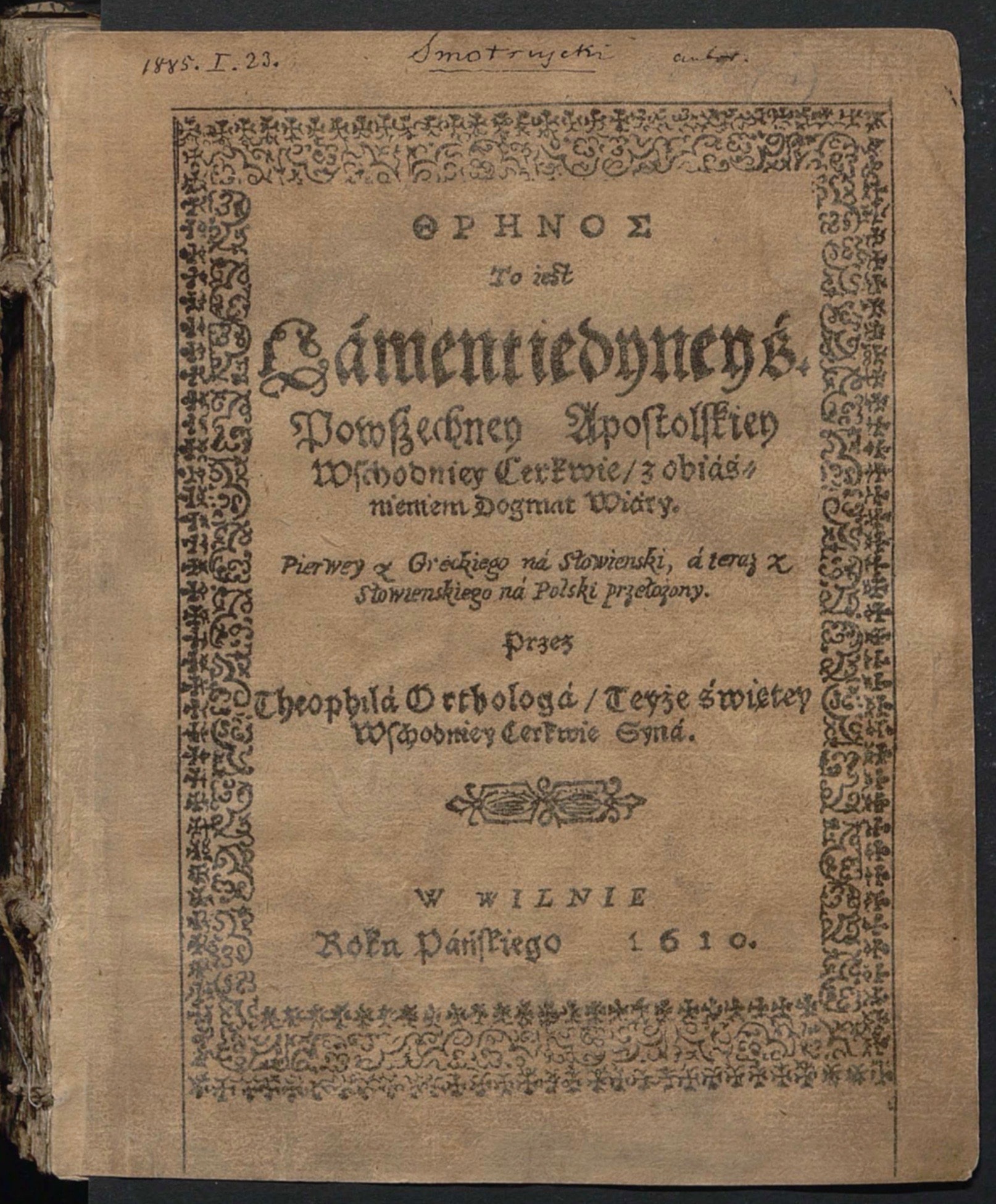

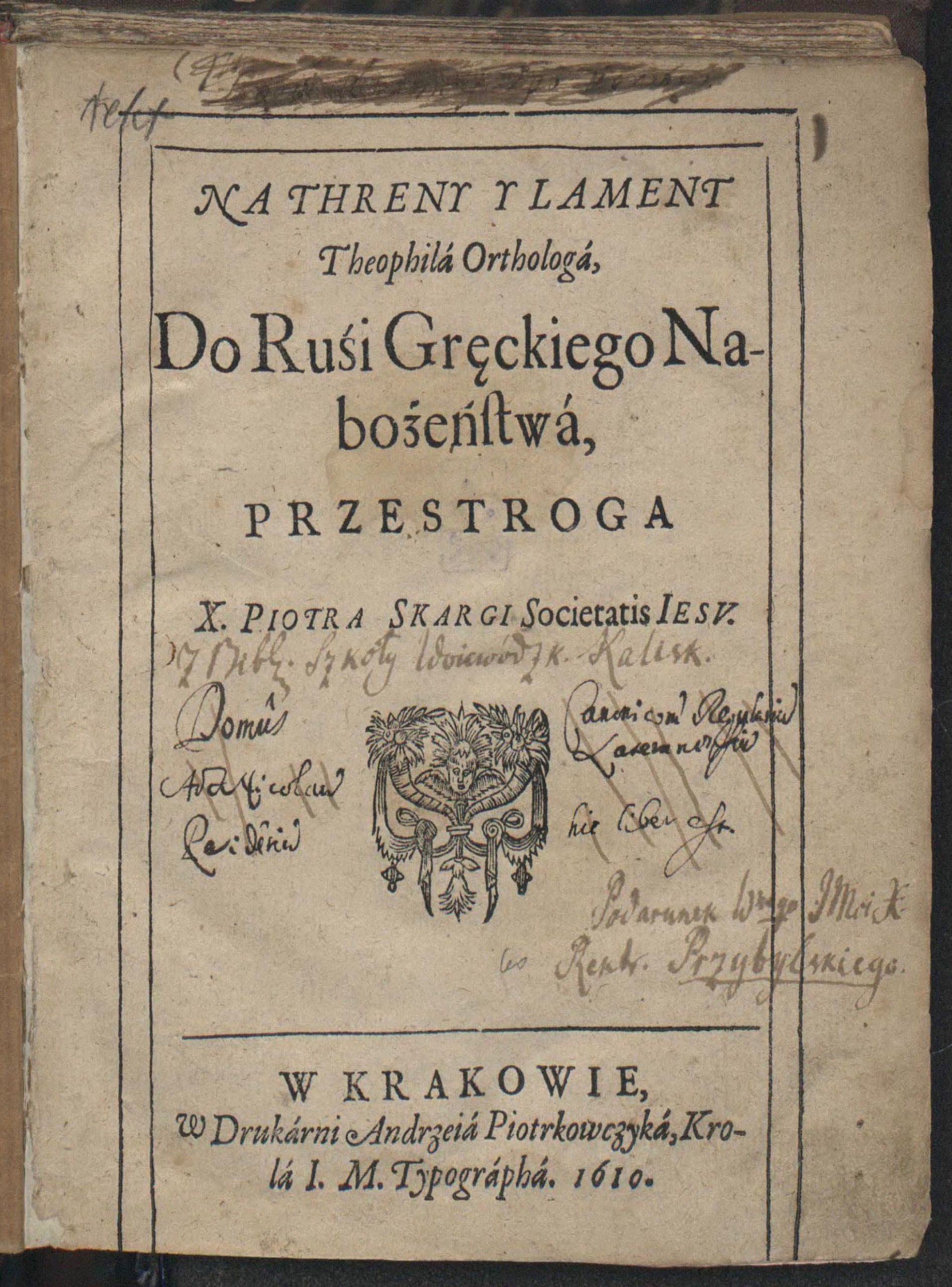

The development of book-publishing in Vilnius in the 17th century had special significance. It was an important factor in polemics between confessions and rites and other social processes.5See: Leonidas Timošenka, “Dvi „Rusios“ ir religinė polemika“, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 75–76; same: Леонід Тимошенко, “Дві „Русі” та релігійна полеміка”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 109. In general, the publications of Vilnius’ publishing centers which involved the religious life of Rus were polemical, occasionally catechetical, though service books constituted the majority (↑). Polemical works, thanks to the significant personal involvement of the authors and publishers, preserve the main details about the particularities of the religious (and not only) life of opponents. The criticism of the polemicists for the most part was directed at concrete opponents: Piotr Skarga, Hypatius Pociej (↑), Stefan Zizanij, and others [3, 4]. Thanks to these publications, we learn about the particularities of the activities of important figures in church history, their views, personal moral traits, etc. (↑) (↑)6Ibid., p. 76–79; same: с. 110–113.

In the 17th century, Vilnius, as a strong sociocultural center, played a role as the center of interconfessional polemics: here were published significant works of Piotr Skarga and Hypatius Pociej, Melecjusz Smotrycki, Antoni Sielawa, and many others whose works were distributed far beyond the borders of Vilnius.7Ibid., p. 73–75; same: с. 105–108. Inasmuch as the formation of the ecclesiastical identity of the Uniates was accompanied by controversies and lively polemics, these works were first of all devoted to theological themes which had already long been exploited in Orthodox-Catholic polemics. As there was an absence in the pre-union period, and also in later times, of certain systematized statements of the teachings of the Orthodox Church, these polemics centered around a list of dogmatic and ritual questions that were far from complete.8See: Маргарита Корзо, Украинская и белорусская катехетическая традиция конца XVI–XVIII вв.: становление, эволюция и проблема заимствований, Москва: Канон+, 2007, 211.

The appearance of the Uniate Church as a consequence of the Union of Brest of 1596 led to the polemic “Two Rus”,9Leonidas Timošenka, op. cit., p. 69; same: Леонід Тимошенко, op. cit., с. 99. though after the Union almost nothing appeared in teachings on the faith and liturgy which would contradict the faith and religious practices of those who had not accepted the Union. It is interesting that, already in the first half of the 17th century, the Orthodox themselves accepted many elements of post-Tridentine sacramentology, though even with this they preserved without change the liturgical rituals.10Тарас Шманько, “Латинізація і окциденталізація: прояви і наслідки”, in: Die Union van Brest (1596) in Geschichte und Geschichtsschreibung: Versuch einer Zwischenbilanz = Берестейська унія (1596) в історії історіографії: спроба підсумку, Hg. Johann Marte, Oleh Turij, Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2008, с. 342–346. Publications of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy of the 17th century, in particular prefaces and commentaries placed in service books, witness to this.

The comparative table below shows some characteristic examples of theological and liturgical-ritual particularities which were the subject of accusations and polemics among the three groups of opponents:

| Religious particularities | Uniates | Orthodox | Roman Catholics |

| The supremacy of the Pope of Rome as successor of Peter, head of the apostles | + | – | + |

| Filioque (a theological formula which expresses the teaching on the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son (a Patre et Filio) compared with the teaching of procession only from the Father (a Patre) | + | – | + |

| Church calendar (Julian/from 1582 Gregorian) | + | + | – |

| Fasts (differences from Roman Catholics) | + | + | – |

| Veneration of the saints (some of them were controversial, for example, Gregory Palamas for Roman Catholics) | + | + | – |

| Eschatology (polemics on “the last things”, faith in the existence of “purgatory”) | + | – | + |

| Eucharistic bread (Roman Catholics use unleavened bread) | + | + | – |

| Married clergy/celibate | + | + | – |

| Administering the sacraments (certain particularities are characteristic of the Eastern Church, for example: communion for newly-baptized infants, chrismation together with baptism, and others) | + | + | – |

As we see in the table, a significant part of religious realities for Uniates of the 17th century were concurrent with the Orthodox, in particular those that related to outward manifestations of the faith. Eventually, in important doctrinal questions we observe a more distinct concurrence of views of the Uniates with the Roman Catholics.

We can affirm that in the 17th century Vilnius was an important factor in the process of crystallizing the new Uniate ecclesiastical identity on all levels of social life . Discussions which were characteristic for the religious environments of Vilnius in those times spread to the whole territory of the Kyivan Metropolitanate (also among the Orthodox), eventually forming the order of the day for church reform in the next period, when the Uniate Church at the local council in Zamość of 1720 codified the basic elements of its identity (↑) (↑) (↑) (↑). Discussions which were characteristic for the religious environments of Vilnius in those times spread to the whole territory of the Kyivan Metropolitanate (also among the Orthodox), eventually forming the order of the day for church reform in the next period, when the Uniate Church at the local council in Zamość of 1720 codified the basic elements of its identity.

Taras Shmanko

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | See: Борис Ґудзяк, Криза і реформа: Київська митрополія, Царгородський патріapхат і ґенеза Берестейської унії, Львів: Інститут історії Церкви ЛБА, 2000, с. 4. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Назар Заторський, «Послання Мисаїла до папи Сикста IV» 1476 року: реконструкція архетипу (series: Київське християнство, т. 15), Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2019, с. 19. |

| 3. | ↑ | See: Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Ukrainietiškoji perspektyva: Kijevo krikščionybės lietuviškųjų ištakų „prisiminimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 243–245; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Українська перспектива”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 365–366. |

| 4. | ↑ | See: Порфирій Підручний, Богдан Пьєтночко, Василіянські генеральні капітули від 1617 по 1636 рік (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 2, т. 55), Рим, Львів: Видавницво Отців Василіян “Місіонер”, 2017. |

| 5. | ↑ | See: Leonidas Timošenka, “Dvi „Rusios“ ir religinė polemika“, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 75–76; same: Леонід Тимошенко, “Дві „Русі” та релігійна полеміка”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 109. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 76–79; same: с. 110–113. |

| 7. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 73–75; same: с. 105–108. |

| 8. | ↑ | See: Маргарита Корзо, Украинская и белорусская катехетическая традиция конца XVI–XVIII вв.: становление, эволюция и проблема заимствований, Москва: Канон+, 2007, 211. |

| 9. | ↑ | Leonidas Timošenka, op. cit., p. 69; same: Леонід Тимошенко, op. cit., с. 99. |

| 10. | ↑ | Тарас Шманько, “Латинізація і окциденталізація: прояви і наслідки”, in: Die Union van Brest (1596) in Geschichte und Geschichtsschreibung: Versuch einer Zwischenbilanz = Берестейська унія (1596) в історії історіографії: спроба підсумку, Hg. Johann Marte, Oleh Turij, Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2008, с. 342–346. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Published in: Vladas Drėma, Dingęs Vilnius = Lost Vilnius = Исчезнувший Вильнюс, Vilnius: Vaga, 1991, p. 34–35, ill. 27. |

| 2. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 3. | [Meletìj Smotrickij], Threnos To iest Lament iedyney ś. Powszechney Apostolskiey Wschodniey Cerkwie, z obiaśnieniem Dogmat Wiary: Pierwej z Greckiego na Słowienski, a teraz z Słowienskiego na Polski przełożony…, Wilno, 1610, [title page]. Held in: BJ, BJ St. Dr. 40951 I (Available at: Jagiellońska Biblioteka Cyfrowa. Uniwersytet Jagielloński, https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=375357, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 4. | [Piotr Skarga], Na Threny Y Lament Theophila Orthologa, Do Rusi Gręckiego Nabożeństwa…, Kraków: Drukarnia Andrzeja Piotrkowczyka, 1610, [title page]. Held in: BJ, BJ St. Dr. 53784 I (Available at: Jagiellońska Biblioteka Cyfrowa. Uniwersytet Jagielloński, https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=374284, accessed: 2021 12 01). |