The Uniate (Greek-Catholic) Church arose at the end of the 16th century, when the episcopate of the Kyivan Orthodox Metropolitanate, hoping to improve the conditions of its faithful in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, approved the decision to transfer under the care of the Roman Apostolic See. In 1596 at a council in Brest, a union was finalized between the Ruthenian Church and Rome (↑). According to its conditions, the hierarchs of the Kyivan Uniate Metropolitanate accepted the Catholic faith; in particular, they recognized the higher authority of the Pope of Rome, though they managed to preserve the Eastern rite. The first Uniate metropolitan was Michael Rohoza (1596–1599). After the council in Brest, the Kyivan Metropolitanate and the Polotsk Archeparchy, and also the Pinsk, Lutsk, Volodymyr, and Cholm eparchies, became part of the Uniate Church.1Борис Ґудзяк, Криза і реформа: Київська митрополія, Царгородський патріхат і ґенеза Берестейської унії, Львів: Інститут історії Церкви ЛБА, 2000, с. 373–310; Леонид Тимошенко, Берестейська унія 1596 р. Навчальний посібник, Дрогобич: Дрогобицький державний педагогічний університет ім. І. Франка, 2004, с. 7–40.

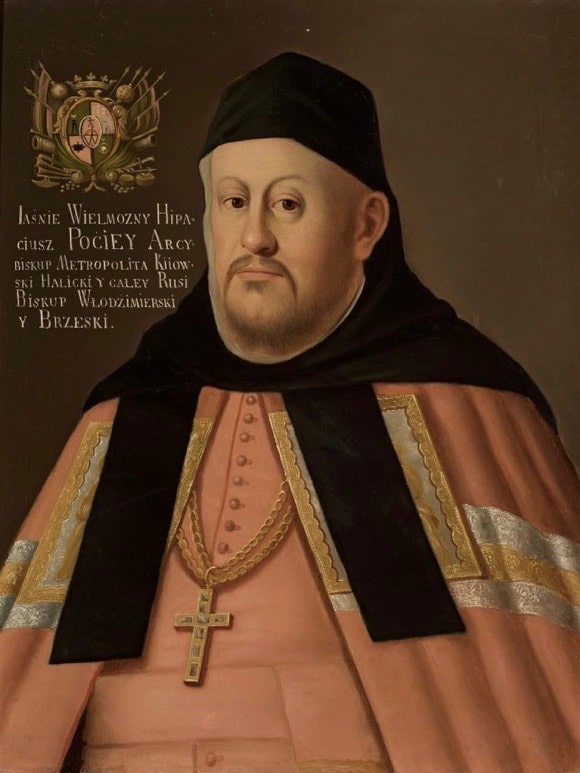

However, not all the bishops and faithful of the Kyivan Metropolitanate supported the Union. The hierarchs of Lviv and Przemyśl remained faithful to the Patriarch of Constantinople. We observe the sharpest conflict between supporters and opponents of the Union in the first decades after its signing, in particular during the rule of Metropolitan Hipatius Pociej (1600–1613) [1] (↑). During his rule, the Uniates managed, in pareticular, to establish control over the churches in Vilnius. At this time, Holy Trinity Monastery in the capital became Uniate, with monks who were to become famous hierarchs – Josaphat Kuntsevych and Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky.2Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir Bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 80–91; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 115–132. The conflict intensified after Patriarch of Jerusalem Theophanes secretly ordained a parallel Orthodox hierarchy in 1620. The culminating moment of this conflict was the murder in Vitebsk in 1623 of Archbishop Kuntsevych of Polotsk, eventually beatified by Pope Urban VIII [2] (↑).3See more: Павло Михайло Кречун, Святий Йосафат Кунцевич (1580–1623) як свідок віри в епосі релігійної контроверсії, Жовква: Місіонер, 2013. Only in 1632 did the authorities of the Commonwealth, in the person of King Władysław IV, officially recognize the parallel existence of two confessional communities in the state.4Сергій Плохій, Наливайкова віра: козацтво та релігія в ранньомодерній Україні, Київ: Критика, 2005, с. 173–176.

One of the most outstanding hierarchs of the period after Brest was Metropolitan Rutsky, who headed the Uniate Church from 1613 to 1637 [3]. At his initiative, in 1617 the Novogrudok chapter was called, at which the Basilian Order was established, which at first united the monasteries mainly on the territories of today’s Belarus and Lithuania. In 1626, he called the first provincial council of the Kyivan Uniate Metropolitanate, which was held in Kobryn. The metropolitan also oversaw the education of candidates for the priesthood and religious life. In particular, at his initiative Rome provided scholarships for Uniates to study at pontifical seminaries. Finally, resisting the transfer of the faithful of his Church to the Latin rite, the metropolitan in 1624 managed to have Pope Urban VIII forbid such “conversions”.5Іриней Іванович Назарко, Київські і Галицькі митрополити, Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1962, с. 17–36; Mirosław Szegda, “Rutski (Welamin Rutski) Jan”, in: Polski słownik biograficzny, t. 33, Krakow, Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich – Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1991–1992, s. 256–260. The reign of Metropolitan Rutsky was also marked by a search for compromise with the hierarchs of the Kyivan Orthodox Metropolitanate (↑).

Events of the middle of the 17th century negatively affected the development of the Uniate Church, above all the Cossack uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1648–1657) and the Russo–Polish War of 1654–1667. The victory of the Cossacks meant the liquidation of the Uniate Church on the territories held by them. Thus, according to the conditions of the Polish–Cossack Treaty of Zboriv (1649), the Union would not exist on the territory of the Cossack state. And so it was no accident that Uniate Bishop of Cholm Jacobus Susza during the Battle of Berestechko (1651) was not in the camp of Khmelnytsky but of King John II Casimir. Also, according to the conditions of the Cossack–Polish Treaty of Hadiach of 1658, the Union was to be liquidated on the territory of the Grand Ruthenian Duchy, which was to become the third component part of the Commonwealth.6Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, Kościoły Wschodnie w państwie polsko-litewskim w procesie przemian i adaptacji: Metropolia kijowska w latach 1458–1795, Lublin, Lwów: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2014, s. 217–227. However, more threatening for the Uniate Church were events on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, where the majority of its faithful lived. Uniate parishes were liquidated on territories occupied by Muscovite soldiers.7Compare: Ирина Герасимова, Под властью русского царя: социокультурная среда Вильны в середине XVII века, Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2015, с. 134–135. The Smolensk Eparchy, which ended up as part of the Muscovite state, in 1654 ceased formally to exist, and its bishop was forced to leave the Smolensk area. Further on, until the end of the existence of the Commonwealth, this see was titular.8T. Kempa, “Smoleńska archidiecezja greckokatolicka”, in: Encyklopedia Katolicka, t. 18, Lublin, 2013, s. 449–450.

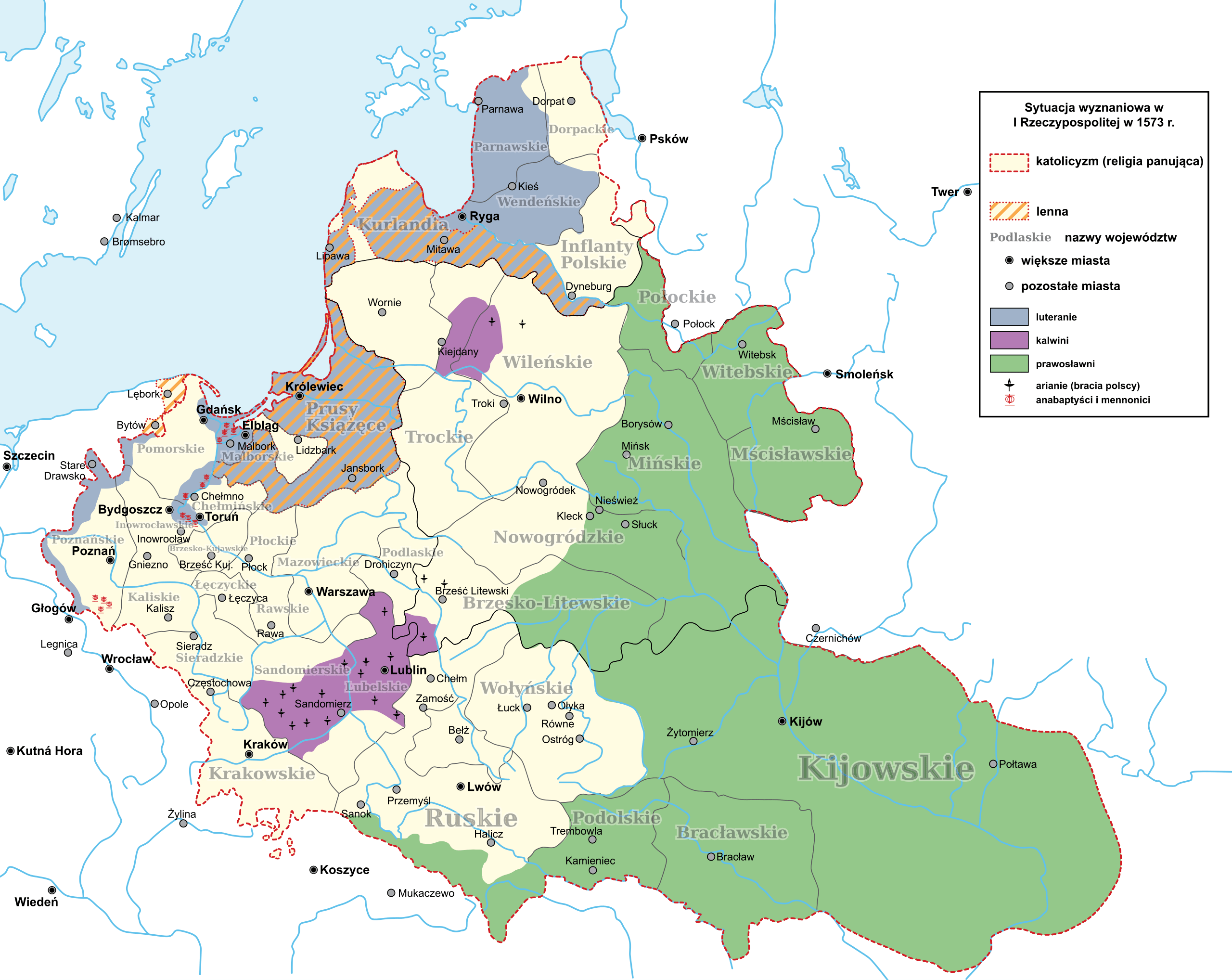

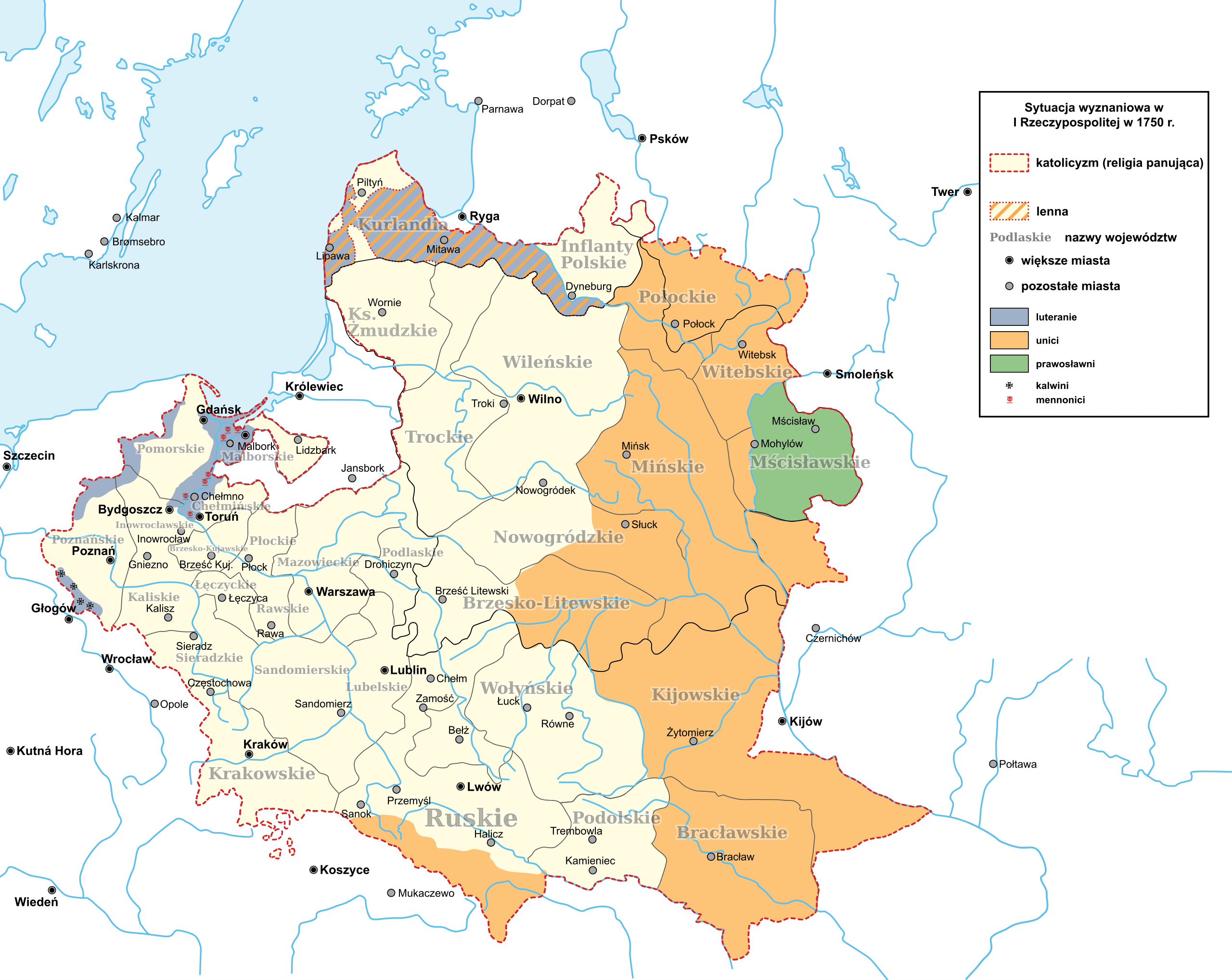

The situation stabilized at the turn of the 18th century, when three more Orthodox eparchies entered into union with the Catholic Church: Przemyśl (1691), Lviv (1700), and Lutsk (1702), and also clergy of right-bank Ukraine (1715).9Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, op. cit., s. 322–324. As a result, the Uniate Church became one of the largest and most numerous confessions of the Commonwealth at that time. For administrative reasons, it was divided into eight archeparchies and eparchies. As of 1772, the number of parishes was approximately 10 thousand, and the number of faithful reached up to 4,5 million [4, 5].

Regardless of territorial growth, the Uniate Church at the start of the 18th century faced a number of problems which needed to be solved immediately. The last provincial council had been held more than 100 years before in Kobryn (1626), and so there was an urgent need to introduce new administrative orders for the normal functioning of the church in new historical conditions. A new provincial council could solve this problem. In addition, after the events of the so-called “new union”, heterogeneity was noticed in the development of older and newer eparchies. The former, mainly on the territories of today’s Belarus and Lithuania, had a Uniate tradition of more than 100 years, with all its positive and negative consequences, such as Latin influences on church life. On the other hand, the new areas, on the territories of today’s Ukraine, continued to maintain centuries-old traditions. So one of the important tasks of the new council was the unification of liturgical and administrative practices of the Uniate Church. Metropolitan Lev Kiszka (1714–1728) [6] called the expected council. It was held in 1720 in Zamość. All the hierarchs of the Kyivan Metropolitanate participated, and numerous representatives of the secular and monastic clergy and also individual lay people. The ritual practices of the Ruthenian Church were codified at this ecclesiastical assembly, in particular the manner of administering the holy sacraments. It established dogmatic norms, set a program for catechizing the faithful, and discussed matters of monasticism and the education of the clergy.10On this shift, see: Юрій Федорів, Замойський Синод 1720 p. (series: Богословія, т. 43), Рим, 1972; Стефан Недельський, Униатский митрополит Лев Кишка и его значение в истории унии, Вильна: губ. тип., 1893. Throughout the first half of the 18th century, thanks to the institution of visitations and eparchial councils, the Kyivan metropolitans and local bishops gradually implemented the decrees of the council of Zamość. The activities of Metropolitan Athanasius Szeptycki (1729–1746) [7] should be particularly noted.

The dynamic development of the Kyivan Uniate Metropolitanate was interrupted as a result of the three divisions of the Commonwealth. A significant part of the territory where the faithful of the Uniate Church lived ended up as part of the Russian Empire. Beginning at the end of the 18th century and throughout the following decades, the state authorities took gradual steps aimed at liquidating this ecclesiastical community in the empire of the Romanovs. The Uniate Church was conclusively liquidated in Russia in 1839, according to the decisions of the council of Polotsk. On the other hand, in the empire of the Habsburgs, Greek-Catholics were able to develop freely. In 1807, the part of the Kyivan Metropolitanate under Austria became the Metropolitanate of Galicia.11Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), вступна стаття та коментарі Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011. From the middle of the 19th century, the further existence of Greek-Catholicism in Central-Eastern Europe was connected only with the Habsburgs (↑).

Oleh Dukh

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Борис Ґудзяк, Криза і реформа: Київська митрополія, Царгородський патріхат і ґенеза Берестейської унії, Львів: Інститут історії Церкви ЛБА, 2000, с. 373–310; Леонид Тимошенко, Берестейська унія 1596 р. Навчальний посібник, Дрогобич: Дрогобицький державний педагогічний університет ім. І. Франка, 2004, с. 7–40. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir Bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 80–91; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 115–132. |

| 3. | ↑ | See more: Павло Михайло Кречун, Святий Йосафат Кунцевич (1580–1623) як свідок віри в епосі релігійної контроверсії, Жовква: Місіонер, 2013. |

| 4. | ↑ | Сергій Плохій, Наливайкова віра: козацтво та релігія в ранньомодерній Україні, Київ: Критика, 2005, с. 173–176. |

| 5. | ↑ | Іриней Іванович Назарко, Київські і Галицькі митрополити, Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1962, с. 17–36; Mirosław Szegda, “Rutski (Welamin Rutski) Jan”, in: Polski słownik biograficzny, t. 33, Krakow, Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich – Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1991–1992, s. 256–260. |

| 6. | ↑ | Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, Kościoły Wschodnie w państwie polsko-litewskim w procesie przemian i adaptacji: Metropolia kijowska w latach 1458–1795, Lublin, Lwów: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2014, s. 217–227. |

| 7. | ↑ | Compare: Ирина Герасимова, Под властью русского царя: социокультурная среда Вильны в середине XVII века, Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2015, с. 134–135. |

| 8. | ↑ | T. Kempa, “Smoleńska archidiecezja greckokatolicka”, in: Encyklopedia Katolicka, t. 18, Lublin, 2013, s. 449–450. |

| 9. | ↑ | Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, op. cit., s. 322–324. |

| 10. | ↑ | On this shift, see: Юрій Федорів, Замойський Синод 1720 p. (series: Богословія, т. 43), Рим, 1972; Стефан Недельський, Униатский митрополит Лев Кишка и его значение в истории унии, Вильна: губ. тип., 1893. |

| 11. | ↑ | Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), вступна стаття та коментарі Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Held in: MNW, 130192 MNW (Available at: Cyfrowe zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/500792, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 2. | Published in: Алексей Сапунов, Витебская старина, т. 5: Материалы для истории Полоцкой епархии, ч. 1, Витебск: В типографии Витебского губернского правления и Г. Малкина, 1888 (insert between pages LXXIV and LXXV). See also: Jolita Liškevičienė, “Ankstyvieji palaimintojo Juozapato Kuncevičiaus portretiniai atvaizdai”, in: Dangiškieji globėjai, žemiškieji mecenatai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 60), sud. Jolita Liškevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 114. |

| 3. | Held in: LNDM, LNDM T 4158 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000001617243?s_id=MfY0X5DJITrVb9li&s_ind=3&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 4. | Published in: Wikimedia Commons, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Religie_w_I_Rz-plitej_1573.svg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 5. | Published in: Ibid., https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Religie_w_I_Rz-plitej_1750.svg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 6. | Held in: LNM, LNM T 1686. |

| 7. | Held in: НМЛ, Відділ графіки, Гд-30. Published in: Wikimedia Commons, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Атанасій_Шептицький._Атанас_Шаптыцкі_(XVIII).jpg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |