Three Vilnius martyrs – saints Anthony, John, and Eustathius (↑) – were buried in the Church of St. Nicholas.1Полное собрание русских летописей, т. 5: Софийская первая летопись, Санкт-Петербург: В типографии Эдуарда Праца, 1851, с. 226. This is the oldest written mention of an Orthodox sacred building in Vilnius. The church was wooden, and after a fire in 1610, which devastated the city, this shrine, which stood at the intersection of today’s Pilies (Castle) and Latako streets, near the still-existing Church of St. Paraskevia, was not rebuilt [1]. The question of the conditions under which the remains of the three Vilnius martyrs later appeared in Holy Spirit Church has still not been answered, because of a lack of sources [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. We have more detailed information about the fate of these remains from the end of the 14th century. In 1368–1372, a great war broke out between Lithuania and Moscow, echoes about which reached even to Constantinople. At the start of the conflict, Patriarch Philotheos of Constantinople unreservedly supported Metropolitan of Kyiv and All Rus Oleksiy, who was in support of the Muscovites. The metropolitan excommunicated from the Church those Ruthenian dukes who were allies of “the fire worshipper”, ruler of Lithuania Algirdas, but he released from such a condemnation those who, breaking an oath given to Algirdas and confirmed by kissing the cross, went to the side of the Muscovites. The angered Lithuanian leader wrote to the patriarch: “Does it happen thus in the world, to nullify kissing the cross?”2Русская историческая библиотека, т. 6: Памятники древне-русскаго канонического права, ч. 1: Памятники XI–XV в., Санкт-Петербург: Тип. Императорской Академии Наук, 1880, с. 137 (№ 24). Duke of Tversk Mykhailo Oleksandrovych complained to Philotheos about similar abuses. Finally, the future metropolitan of all Rus, Kypriyan (1375–1406), delegated by the patriarch, was sent from Constantinople so that, on site, he could mend the confused relations of dukes on the territories from Vilnius to Moscow. Arriving in Lithuania in winter 1373–1374, he learned of the local martyrs. It is likely that Kypriyan himself took the most care so that part of the relics of the three Vilnius martyrs were brought to Constantinople, where in 1374 Patriarch Philotheos received them. The hierarch made sure that prayers were composed and icons written in honour of the new martyrs. The transfer of the relics of the martyrs and their liturgical veneration was comparable to official canonization.3Darius Baronas, Trys Vilniaus kankiniai: gyvenimas ir istorija, Vilnius: Aidai, 2000, p. 85–92.

Grand Duke Algirdas himself gave permission for the transfer of the incorruptible remains. Clearly, on this occasion, at the request of Kypriyan (and perhaps also of his wife, Ulyana), he freed prisoners who were jailed during the Lithuanian-Moscow war.4Русская историческая библиотека…, с. 181–182. Some of the prisoners returned to northeastern Ruthenian lands, and some remained to live in Vilnius [7]. The latter themselves “asked, beseeching the duke, that he look on their request and give them some place where they would be able to build a holy church in which they would gather. And he, attentively listening to them, prophesied: ‘The place that you ask for is not worthy of a church, for there is a valley there and darkness.’ Instead, he indicated the place of the hanging. It was worthy, because high and bright. They gladly built a church there, in the name of the holy and life-giving Trinity, and praise will there be given to [the Trinity].”5Darius Baronas, op. cit., p. 257–259. Given the circumstances of the appearance of this shrine, we can call Grand Duke Algirdas the founder of Holy Trinity Church.

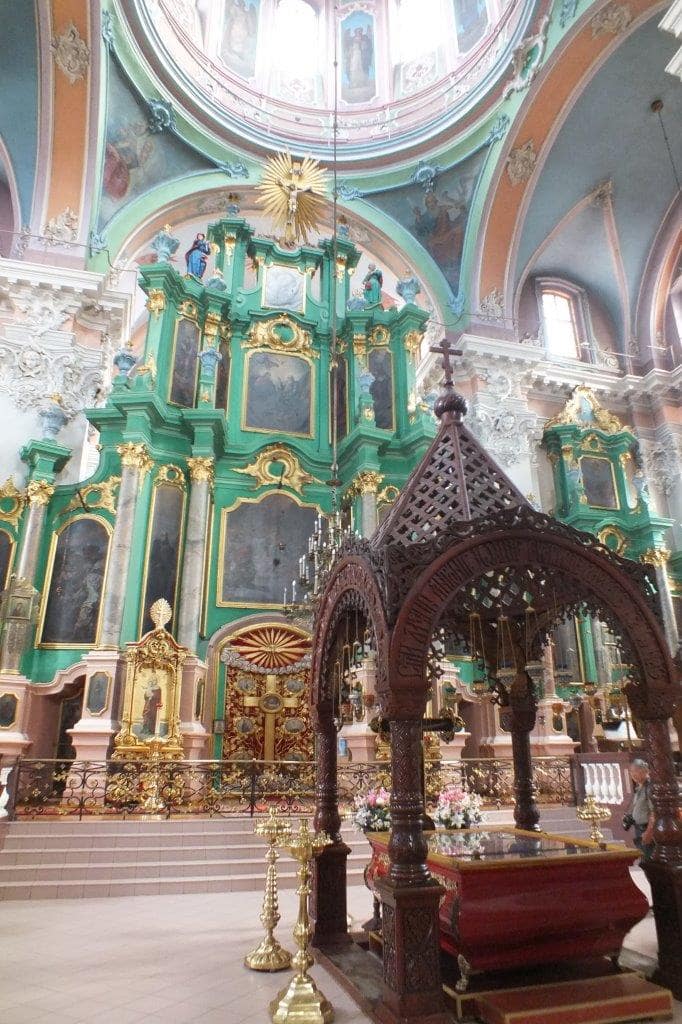

Near the wooden Holy Trinity Church built in 1374, a monastic community formed in time. Because of later re-building and additions, today no archeological traces of the early period can be found, that is, from the end of the 14th to the start of the 15th centuries. The oldest mentions of a monastery founded near the church date to 1460 (↑).6Описание рукописного отделения Библиотеки Императорской Академии Наук, т. 1: I. Книги Священнаго писания и II. Книги богослужебные, сост. В. И. Срезневский, Ф. И. Покровский, Санкт-Петербург: Типография Императорской Академии Наук, 1910, с. 34. From the 1480s, Holy Trinity Monastery is more and more often mentioned in Lithuanian metrics.7Lietuvos Metrika. Knyga Nr. 4 (1479–1491). Užrašymų knyga 4 = Lithuanian Metrica. Book of Inscriptions 4 (1479–1491), par. Lina Anužytė, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2004, p. 83, 86. Even at that time Archimandrite Makariy headed this monastic community. Such a title for the superior of the monks demonstrates that the monastic center was already formed; the head took part in administrating structures of the Kyivan Metropolitanate. The significance of the monastery itself and also its head is witnessed by the fact that this Makariy in 1495 was elected metropolitan of Kyiv. Having assumed the metropolitan see, he continued to take care of matters of church administration in Vilnius and Kyiv. Not far from Mozyr, Metropolitan Makariy was seized by Crimean Tatars and killed (1 May 1497), becoming yet another martyr for the faith [8, 9].8Полное собрание русских летописей, т. 35: Летописи белорусско-литовские, сост. Н. Н. Улащик, Москва: Наука, 1980, с. 124. His activities regarding the revitalizing of relations between Kyiv and Vilnius appeared not be in vain. There was a strong impetus to strengthening these relations in 1514, when, in gratitude to God for victory in the battle near Orsha, Grand Hetman of Lithuania Konstanty Ostrogski funded a new, large, now brick, Holy Trinity Church (↑).

Darius Baronas

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Полное собрание русских летописей, т. 5: Софийская первая летопись, Санкт-Петербург: В типографии Эдуарда Праца, 1851, с. 226. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Русская историческая библиотека, т. 6: Памятники древне-русскаго канонического права, ч. 1: Памятники XI–XV в., Санкт-Петербург: Тип. Императорской Академии Наук, 1880, с. 137 (№ 24). |

| 3. | ↑ | Darius Baronas, Trys Vilniaus kankiniai: gyvenimas ir istorija, Vilnius: Aidai, 2000, p. 85–92. |

| 4. | ↑ | Русская историческая библиотека…, с. 181–182. |

| 5. | ↑ | Darius Baronas, op. cit., p. 257–259. |

| 6. | ↑ | Описание рукописного отделения Библиотеки Императорской Академии Наук, т. 1: I. Книги Священнаго писания и II. Книги богослужебные, сост. В. И. Срезневский, Ф. И. Покровский, Санкт-Петербург: Типография Императорской Академии Наук, 1910, с. 34. |

| 7. | ↑ | Lietuvos Metrika. Knyga Nr. 4 (1479–1491). Užrašymų knyga 4 = Lithuanian Metrica. Book of Inscriptions 4 (1479–1491), par. Lina Anužytė, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2004, p. 83, 86. |

| 8. | ↑ | Полное собрание русских летописей, т. 35: Летописи белорусско-литовские, сост. Н. Н. Улащик, Москва: Наука, 1980, с. 124. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Held in: БАН, Отдел рукописей, БАН 31.7.30/1, l. 431. Published in: Лицевой летописный свод XVI века. Русская летописная история, book 8: 1343–1372 гг. [Остермановский первый том], Москва: ООО фирма „АКТЕОН”, 2014, p. 49. |

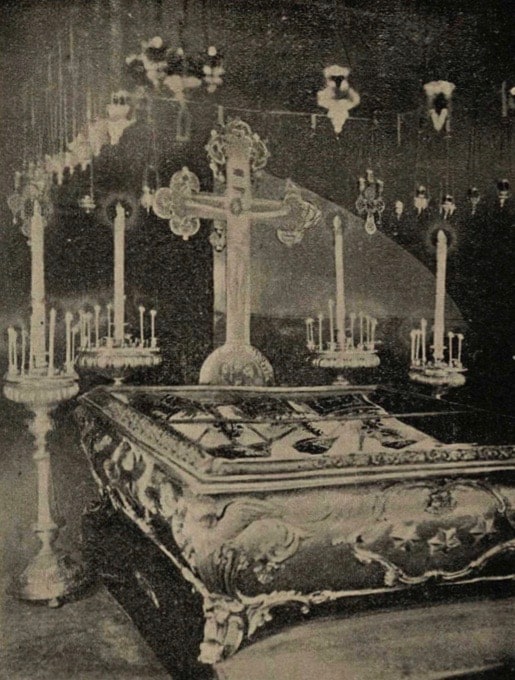

| 2. | Памятники русской старины в западных губерниях империи, т. 5: Вильна, Санкт-Петербург: [М-во внутр. дел], 1870, ил. 15. Held in: LNDM, LNDM G 804/12 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000006367878?s_id=q5xKQycWRiPmRzUx&s_ind=12654&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 3. | Published in: А. А. Виноградов, Православная Вильна, Вильна: тип. Штаба Вилен. воен. окр., 1904, (insert between pages 2 and 3); А. А. Виноградов, Путеводитель по городу Вильне и его окрестностям, Вильна: тип. Штаба Вилен. воен. окр., 1904, (insert between pages 44 and 45). |

| 4. | Held in: KPC PB. Published in: “Vilniaus miesto gynybinės sienos Medininkų-Subačiaus vartų dalies, Šv. Teresės bažnyčios ir basųjų karmelitų vienuolyno, Šv. Dvasios cerkvės ir vienuolyno komplekso Šv. Dvasios cerkvė” [unikalus kodas: 27311], in: Kultūros vertybių registras, available at: https://kvr.kpd.lt/#/static-heritage-detail/95D19DDE-2096-42CF-9712-46BE6101C813, photograph number 7.35 or 37, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 5. | Ibid., photograph number 7.96 or 97. |

| 6. | Ibid., photograph number 7.97 or 98. |

| 7. | Photographers Rytis Jonaitis and Irma Kaplūnaitė. Held in: LNM, AV 98:115. Published in: Irma Kaplūnaitė, Vilniaus senojo miesto vietoje su priemiesčiais (25504), sklype Bokšto g. 6, 2012 m. vykdytų detaliųjų archeologijos tyrimų ataskaita, d. 1: Tekstas, tyrimų ir radinių nuotraukos, priedai, 2014 (Held in: Library of the Institute of History of Lithuania, Manuscript Division, f. 1, file no. 6684); Rytis Jonaitis, Irma Kaplūnaitė, Senkapis Vilniuje, Bokšto gatvėje. XIII–XV a. laidosenos Lietuvoje bruožai, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2021, p. 239–290 (il. 125). |

| 8. | Photographer Salvijus Kulevičius, 2017. Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 9. | Private collection of Stepan Almes. |